The Work Place Violence Its Types and Prevention In Nursing. Workplace violence against healthcare personnel refers to any physical, sexual, or psychological harm committed by a patient or visitor in the workplace.

What Is Work Place Violence Its Types and Prevention In Nursing

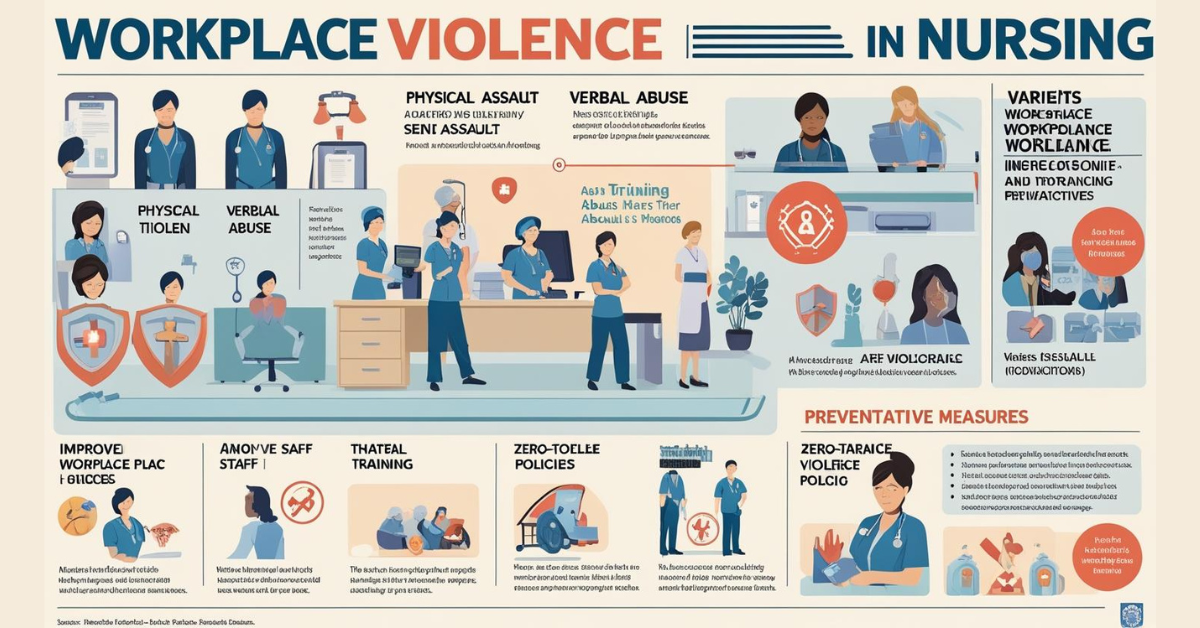

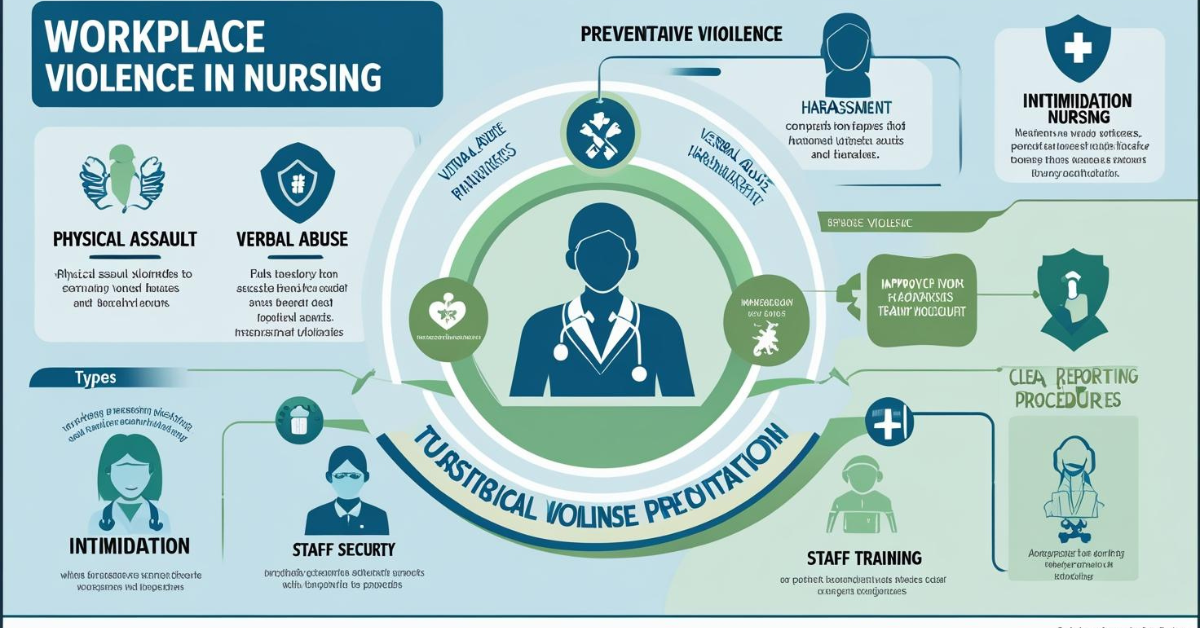

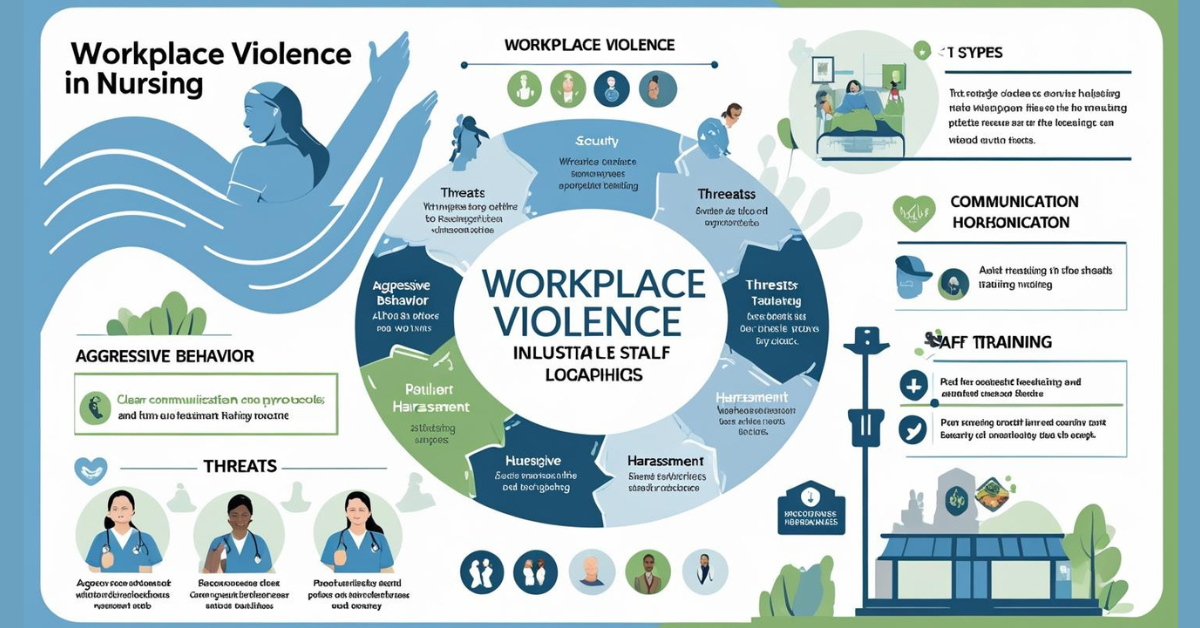

Workplace violence is a recognized risk in the healthcare sector. Workplace violence includes any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening or disruptive behavior in the workplace.

By implementing preventative measures such as comprehensive policies, training programs, effective reporting systems, safety measures, regular risk assessments, communication channels, and maintaining a healthy work environment, companies can significantly reduce the risk of workplace violence.

Types of Violence

There are several different types of workplace violence: nurse-to-nurse violence, third party violence, nurse-to-patient violence, patient-to-nurse violence, organizational violence, external violence, sexual harassment, and mass trauma or natural disasters.

Nurse-to-Nurse Violence

Nurse-to-nurse violence, or physical or nonphysical violence between or among nurses who have a workplace relationship, has many other names, such as lateral violence, horizontal violence, and vertical violence. Although these terms are used interchangeably, each has a slightly different meaning, although all can be considered forms of bullying and incivility. Nurse-to-nurse violence falls under the NIOSH type 3 classification and is very common in health care.

Lateral violence (also known as horizontal violence) consists of bullying or incivility between two or more nurses at the same level. For example, Susan, a registered nurse, is at the end of her shift and is told that Barb will be her relief. Susan says to several other nurses, “I hate to give report to Barb. She asks so many annoying questions.” When Barb arrives for report, Susan rudely says, “Don’t ask me any questions. I’m tired and want to go home!” The nurses who overhear all giggle. In this situation, Susan was gossiping about Barb and also spoke to her rudely. Both are examples of lateral violence.

In contrast, vertical violence consists of bullying or incivility between a nurse subordinate and someone at a higher level (e.g., a manager or charge nurse). For example, in a staff meeting, the nurse leader and manager is explaining to everyone about an upcoming change related to documentation. Several staff nurses ask about who made the decision to make the change. The nurse leader and manager rolls her eyes, sighs loudly, and says, “It was my decision, and I do not appreciate you questioning me!”

In this situation, the nurse leader and manager was disrespectful to the nurses in the meeting. In addition, the nurse leader and manager made an important decision without discussing it with the staff members, those who are impacted most by the decision. When staff members are not treated with respect, they will not feel valued or appreciated. Repeated experiences such as this can lead to avoidance, communication blocks, and distractions, which ultimately impact patient safety (Lucian Leape Institute, 2013).

Violence among nurses negatively affects the environment of care; roughly 60% of new graduate nurses leave their first nursing position within a year as a result of experiencing workplace violence (Embree & White, 2010). Nurse-to-nurse violence results in a negative community, emotional and physical aftermath, undesirable effects on patient care, and injured associations among coworkers.

Nurses must keep in mind that they are called to create “an ethical environment and culture of civility and kindness, treating colleagues, coworkers, employees, students, and others with dignity and respect” (ANA, 2015a, p. 4).

Third-Party Violence

Third-party violence refers to violence that is witnessed directly or indirectly by others. This often occurs when another witnesses nurse-to-nurse violence. The person who observes the violence, the third party, can experience the same harm as the victim of the violence.

When a nurse observes another nurse being rude or disrespectful to a coworker, he or she can experience the same physiological and/or psychological effects as the victim of the actual violence. Research shows that third-party violence jeopardizes the confidence and security of the individual witness, so the perpetrator is actually inflicting harm on secondary victims (Hockley, 2014).

Nurse-to-Patient Violence

Nurse-to-patient violence occurs when nurses are violent toward those in their professional care, with a resulting violation of the nurses’ code of ethics (Hockley, 2014). The most blatant example of this type of violence is a nurse hitting a patient. Other examples can be using restraints without an order and refusing to administer pain medication in a timely manner.

Often this type of violence involves nurses violating professional boundaries (i.e., asking a patient on a date). Nurses must recognize and maintain boundaries that establish appropriate limits on the nurse-patient relationship. If professional boundaries are jeopardized, nurses have an ethical responsibility to seek assistance and/or remove himself or herself from the situation (ANA, 2015a)

Patient-to-Nurse Violence

Patient-to-nurse violence involves a patient or family member being violent toward a nurse and falls under the NIOSH type 2 category. A patient hitting or biting a nurse is an example of this type of violence. A family member yelling at a nurse is another example. Factors such as acute disease states, alcohol or drug intoxication, self-harming behavior, or a present exacerbation of a psychiatric disease are major contributors to this type of workplace violence. Intensified states of emotion in patients or their families (e.g., nervousness, distress, despair, sorrow, irritation, or loss of control) are also considered contributing factors to the incidence of workplace violence.

Typically, male patients or family members are more likely to execute both physical violence and verbal violence toward nurses who are women (Hockley, 2014). Incidences of assault against male nurses are more likely to occur in a psychiatric setting, whereas female nurses are more likely to be attacked in other specialty areas, with the highest occurrence of violence taking place within the emergency department and psychiatric care environments (Child & Mentes, 2010).

Organizational Violence

Organizational violence affects the entire health-care organization and occurs as a result of a changing work environment (Hockley, 2014). For example, excessive workloads and unsafe working conditions can be considered forms of workplace violence (International Council of Nurses, 2006). Often, this type of violence tarnishes the reputation of the organization as well as negatively impacts the employees.

External Violence

External violence is perpetrated by outside persons entering the workplace or when nurses are going to or from the workplace. This type of violence is type 1 according to NIOSH. It is usually random, and the perpetrators typically have criminal intent, such as rape, assault, armed robbery for drugs, or gang reprisals in emergency departments (Hockley, 2014).

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment has not received as much attention in recent nursing literature as workplace violence, yet it is still prevalent. Sexual harassment includes “inappropriately friendly behavior, sexually based verbal comments, vulgar, sexual language or inappropriate jokes or stories; unwelcome advances or requests for sexual favors; unwanted physical contact of a sexual nature; and sexual innuendo” (McNamara, 2012, p. 536).

In a worldwide sample of 151,347 nurses, approximately one-fourth reported experiencing sexual harassment (Spector, Zhou, & Che, 2014). Sexual harassment in nursing occurs between nurses, between nurses and their supervisors, and between nurses and patients or family members. Many nurses take sexual harassment in stride, view it as part of the job, and decide not to report it.

Nurses and nursing students have a right to a workplace free of sexual harassment, and there are legal protections. It falls on nurse leaders and managers to be knowledgeable of federal and state legislation and to ensure that policies and procedures are in place and maintained to protect staff from sexual harassment.

Mass Trauma or Natural Disasters

Workplace violence can also come in the form of mass trauma, such as biochemical attacks or terrorist attacks, and natural disasters. Nurses’ work during mass trauma or natural disasters can be extremely stressful and has the potential to cause serious health and mental health issues. However, little research has been done on this type of violence (Hockley, 2014).

Contributing and Risk Factors

Workplace violence continues to occur for three reasons: because it can, because it is modeled, and because it is left unchecked (McNamara, 2012). TJC (2012) suggests that disruptive behaviors that constitute workplace violence stem from individual and systemic factors. Some individuals who may lack interpersonal coping or conflict management skills can be more prone to disruptive behavior than others.

Systemic factors include increased productivity demands, cost containment, and stress from fear of litigation. Inadequate information between organization leader ship and staff and a lack of staff involvement in decisions can also contribute to workplace violence (Longo, 2012). Another contributing factor is that nurses have been expected to cope with violence and accept abuse as part of the job.

The pressure, be it spoken or unspoken, put on nurses to remain silent about workplace violence (e.g., more than 80% of incidents of workplace violence go unreported [American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 2016]) hampers development and implementation of strategies to prevent it. In terms of which nurses are more at risk for workplace violence, risk factors involve age, gender, nursing experience, and present or previous history of involvement in an abusive relationship.

Younger and less experienced nurses are more likely to be victims of workplace violence. This reality may be attributed to the fact that older, more experienced nurses are in positions of management and experience fewer patient and family interactions than younger novice nurses. Nurses in the emergency department also face an increased risk of violence, mostly related to the degree of accessibility (i.e., 24-hour access), amplified noise level, diminished security, elevated stress, and extended wait times (Child & Mentes, 2010).

Consequences

As a result of the underreporting of workplace violence incidents, there is debate on its prevalence. Research has shown that as few as 16% of nurses actually report acts of workplace violence. Some nurses ignore workplace violence because of a lack of knowledge, whereas others fear repercussion if they report it (Kaplan, Mestel, & Feldman, 2010).

Lack of time and inadequate administrative support have been identified as reasons that nurses fail to report events; 50% of nurses who reported acts of violence felt as if the hospital administrators neglected to act on it and in some instances that management was punitive and insinuated that the staff instigated the acts of violence (Chapman, Styles, Perry, & Combs, 2010). Nurses who have been exposed to workplace violence perceive that organizational factors such as the environment of care as well as specific personal factors establish the frequency and character of workplace violence (Chapman et al., 2010).

However, the ANA (2015a) contends that any form of workplace violence puts the nursing profession in jeopardy. Further, the ANA contends that those who witness work place violence and do not acknowledge it, choose to ignore it, or fail to report it are actually perpetuating it (p. 2). There are many personal consequences of workplace violence, and they can be cumulative. Nurses who are victims of workplace violence can experience physical and psychological problems as a result.

Some physical effects include frequent headaches, gastrointestinal upset, weight loss or gain, sleep disturbances, hypertension, and decreased energy (Longo, 2012). The psychological effects may include stress, anxiety, nervousness, depression, frustration, mistrust, loss of self-esteem, burnout, emotional exhaustion, and fear (Longo, 2012). Health-care organizations can also be affected. Workplace violence can result in increased absenteeism, decreased worker satisfaction, and increased attrition.

In addition, financial issues arise from increased use of sick pay and paying replacement workers (Longo, 2012). Environments of care in which nurses perceive that they have a lack of control, work under authoritarian managers, have limited resources, and feel persecuted will lead to low morale and a toxic work environment, which fosters work place violence. In contrast, a supportive environment with positive teamwork mitigates workplace violence (Embree & White, 2010; Hegney, Tuckett, Parker, & Eley, 2010).

Strategies to Prevent Workplace Violence

There are strategies nurse leaders and managers can use to prevent specific kinds of workplace violence, as well as in general. First, nurse leaders and managers must ex amine the workplace for the presence of elements of an unhealthy environment such as tolerance of incivility and bullying, high levels of stress and frustration among staff members, and a lack of trust among staff members and between staff and management.

Next, increasing awareness of workplace violence by providing information at staff meetings can help prevent workplace violence. Nurse leaders and managers can model and promote positive and professional behaviors to foster a healthy environment. In addition, nurse leaders and managers should support the development of organizational zero-tolerance workplace violence programs and policies. Methods to prevent and overcome acts of lateral violence between nurses specifically should also focus on strengthening communication among providers of care.

A significant source of stress for all nurses, especially a new nurse entering practice, lateral violence among nurses prohibits the delivery of quality health care. Nurse managers and lead ers must ensure that communication is open, nonbiased, and respectful at all times. Nurses must be able to trust their colleagues and believe that they work within a team. Once an incident of workplace violence occurs, nurse leaders and managers should handle the situation by acknowledging the victim, confronting the perpetrator, and informing the perpetrator that such behavior will not be tolerated.

In cases of patient-to-nurse violence, evidence suggests that implementing measures to decrease the incidence of patient and family member attacks on health-care providers has succeeded. First, violence prevention training for staff can curve the onset of an act of violence within the health-care environment and in fact decrease the overall rates of violent incidents at the hands of patients and family members (Kling, Yassi, Smailes, Lovato, & Koehoorn, 2011). Second, the Alert System has been implemented and found to facilitate a reduction of the prevalence of work place violence.

The system is a violence prevention intervention that includes a risk assessment form nurses can use to assess patients and identify those at an increased risk of violence on admission into an acute care setting; if a patient is identified as such, the chart is then flagged for other providers of care so they are aware and can take precautions (e.g., wearing a personal alarm while caring for the patient, having security within the vicinity, not having objects that may potentially be used as a weapon close to the patient surroundings, and not caring for the patient without an additional staff member present) (Kling et al., 2011).

To prevent workplace violence on a wider scale, an environment of care that fosters positive collegial relationships, facilitates open communication among health-care providers, and adopts a zero-tolerance policy for abuse must be cultivated. Nurse leaders and managers can enable an environment of safety that will minimize harm to patients and providers by embracing factors that create a culture of safety, such as effective communication and an organizational reporting system for incidences of workplace violence, as well as valuing the influences that positively impact the quality and safety of the delivery of patient care (Cronenwett et al., 2007).

There are several resources that nurse leaders and managers can use to ensure a healthy, safe work environment. TJC (2012) set standards for addressing workplace violence or behaviors that undermine a culture of safety as well as addressing the fact that behavior that intimidates others can create an environment of hostility and disrespect that affects morale, increases staff turnover, and leads to distractions and errors, all of which compromise patient safety (McNamara, 2012).

Nurse leaders and managers can also use the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements (2015a), the ANA Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (2015b), and the ANA position statement Incivility, Bullying, and Workplace Violence (2015c) as guide lines to create and sustain a healthy work environment free of workplace violence. In addition, OSHA Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Services Workers (OSHA, 2015) is another valuable resource for nurse leaders and managers and provides violence prevention guidelines and effective ways to reduce risk of violence in the workplace.

Nurse leaders and managers must also remember that creating and sustaining a healthy work environment is not their sole responsibility, but rather all nurses are accountable for a healthy work environment. Nurses have an individual responsibility to focus on what they can do to affect a healthy work environment. In a healthy work environment, professionals can use skilled communication to achieve positive outcomes. A model was developed for becoming a skilled communicator and encouraging nurses to become aware of self-deception, reflective, authentic, mindful, and candid (Kupperschmidt, Kientz, Ward, & Reinholz, 2010).

The five factors with operational definitions are displayed in Table 13-1. Nurse leaders and managers can also look to another model that identifies and addresses quality-of-life issues, including workplace violence, for nurses (Todaro-Franceschi, 2015). The model uses the acronym ART, which stands for Acknowledging a problem, Recognizing choices and choosing purposeful actions to take, and Turning toward self and others to reconnect with self and the environment in a way that fosters contentment.

This model urges nurses to speak up and advocate for themselves rather than remaining silent or “going along to get along,” which results in a lose-lose situation. Effective nurse leaders and managers understand that their staff members “want to be heard, understood, and respected for what they bring to the workplace” (Todaro-Franceschi, 2015).

Conclusion

An unhealthy work environment lacks safe patient mobility equipment, ignores nurse fatigue, and encourages disruptive behaviors. Errors and preventable adverse outcomes, which are common in such environments, contribute to poor patient satisfaction, increase cost of care, and negatively impact nurse retention. All nurses, regardless of role, have a responsibility to contribute to a safe and healthy environment that encourages respectful interactions with patients, families, and colleagues (ANA, 2015a).

Nurses at all levels and in all settings have a moral obligation to collaborate to create an environment that fosters respect and is free from workplace violence. Nurse leaders and managers have an ethical and legal responsibility to provide a safe and healthy work environment. An environment of mutual respect promotes joy and meaning at work and enables nurses to be more satisfied and able to deliver more effective care. All factors that contribute to an unhealthy work environment must be addressed to ensure quality and pro mote a culture of safety for both patients and staff. Otherwise, sustaining a culture of safety becomes impossible.

Read More:

https://nurseseducator.com/didactic-and-dialectic-teaching-rationale-for-team-based-learning/

https://nurseseducator.com/high-fidelity-simulation-use-in-nursing-education/

First NCLEX Exam Center In Pakistan From Lahore (Mall of Lahore) to the Global Nursing

Categories of Journals: W, X, Y and Z Category Journal In Nursing Education

AI in Healthcare Content Creation: A Double-Edged Sword and Scary

Social Links:

https://www.facebook.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.instagram.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.pinterest.com/NursesEducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/nurseseducator/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Afza-Lal-Din

https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=F0XY9vQAAAAJ

I just like the valuable information you provide to your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and take a look at again here frequently. I’m reasonably certain I will be informed many new stuff proper here! Best of luck for the following!

Thank you, I’ve recently been searching for information approximately this subject for ages and yours is the greatest I’ve discovered till now. But, what about the bottom line? Are you certain concerning the supply?

Thank you a lot for sharing this with all people you really recognize what you are speaking approximately! Bookmarked. Please additionally discuss with my site =). We will have a hyperlink exchange contract among us!

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to this fantastic blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to brand new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group. Talk soon!

I have recently started a web site, the info you offer on this web site has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

I?¦m no longer positive the place you’re getting your information, but great topic. I must spend a while studying much more or working out more. Thank you for magnificent information I used to be looking for this info for my mission.

hello!,I love your writing so much! proportion we keep up a correspondence more about your post on AOL? I require a specialist on this house to resolve my problem. Maybe that is you! Looking ahead to look you.

I’ve recently started a site, the info you provide on this web site has helped me greatly. Thanks for all of your time & work.

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to send you an email. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great blog and I look forward to seeing it expand over time.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to contribute & help other users like its aided me. Great job.

I’ve been surfing online more than three hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the net will be much more useful than ever before.