What are Qualitative Research Accounts and Storytelling: Complete Guide to the Ethnographic Approach. However, the core ideas are fundamental to the ethnographic method, which is a key form of qualitative research, and which naturally involves detailed descriptions and narrative construction (storytelling) of a particular culture or social group.

Complete Guide to the Ethnographic Approach: Qualitative Research Accounts and Storytelling

The rationale of much of this post is in the interpretive, ethnographic paradigm which strives to view situations through the eyes of participants, to catch their intentionality and their interpretations of frequently complex situations, their meaning systems and the dynamics of the interaction as it unfolds.

This is akin to the notion of ‘thick description’ from Geertz (1973) and his predecessor Ryle (1949). The post proceeds in several stages: firstly, we set out the characteristics of the ethnographic approach; secondly, we set out procedures in eliciting, analyzing and authenticating accounts; thirdly, we introduce handling qualitative accounts and their related fields of:

(a) network analysis

(b) discourse analysis; fourthly, we introduce accounts; finally, we review the strengths and weaknesses of ethnographic approaches.

We recognize that the field of language and language use is vast, and to try to do justice to it here is the ‘optimism of ignorance’ (Edwards, 1976). Rather, we attempt to indicate some important ways in which researchers can use accounts in collecting data for their research.

The field also owes a considerable amount to the communication theory and speech act theory of Austin (1962), Searle (1969) and, more recently, Habermas (e.g. 1979, 1984). In particular, the notion that there are three kinds of speech act (locutionary—saying something; illocutionary—doing something whilst saying something; and perlocutionary—achieving something by saying something) might commend itself for further study.

What Is Ethnographic Research

Although each of us sees the world from our own point of view, we have a way of speaking about our experiences which we share with those around us. Explaining our behavior towards one another can be thought of as accounting for our actions in order to make them intelligible and justifiable to our fellows.

Thus, saying ‘I’m terribly sorry, I didn’t mean to bump into you’, is a simple case of the explication of social meaning, for by locating the bump outside any planned sequence and neutralizing it by making it intelligible in such a way that it is not warrantable, it ceases to be offensive in that situation (Harré, 1978).

Accounting for actions in those larger slices of life called social episodes is the central concern of participatory psychology which focuses upon actors’ intentions; their beliefs about what sorts of behavior will enable them to reach their goals, and their awareness of the rules that govern those behaviors.

Studies carried out within this framework have been termed ‘ethogenic’, an adjective which expresses a view of the human being as a person, that is, a plan-making, self-monitoring agent, aware of goals and deliberately considering the best ways to achieve them. Before discussing the elicitation and analysis of accounts we need to outline the ethogenic approach in more detail. This we do by reference to the work of one of its foremost exponents, Rom Harré (1974, 1976, 1977a, 1977b, 1978).

The Ethnographic Approach

Five Core Principles of Ethnographic Research

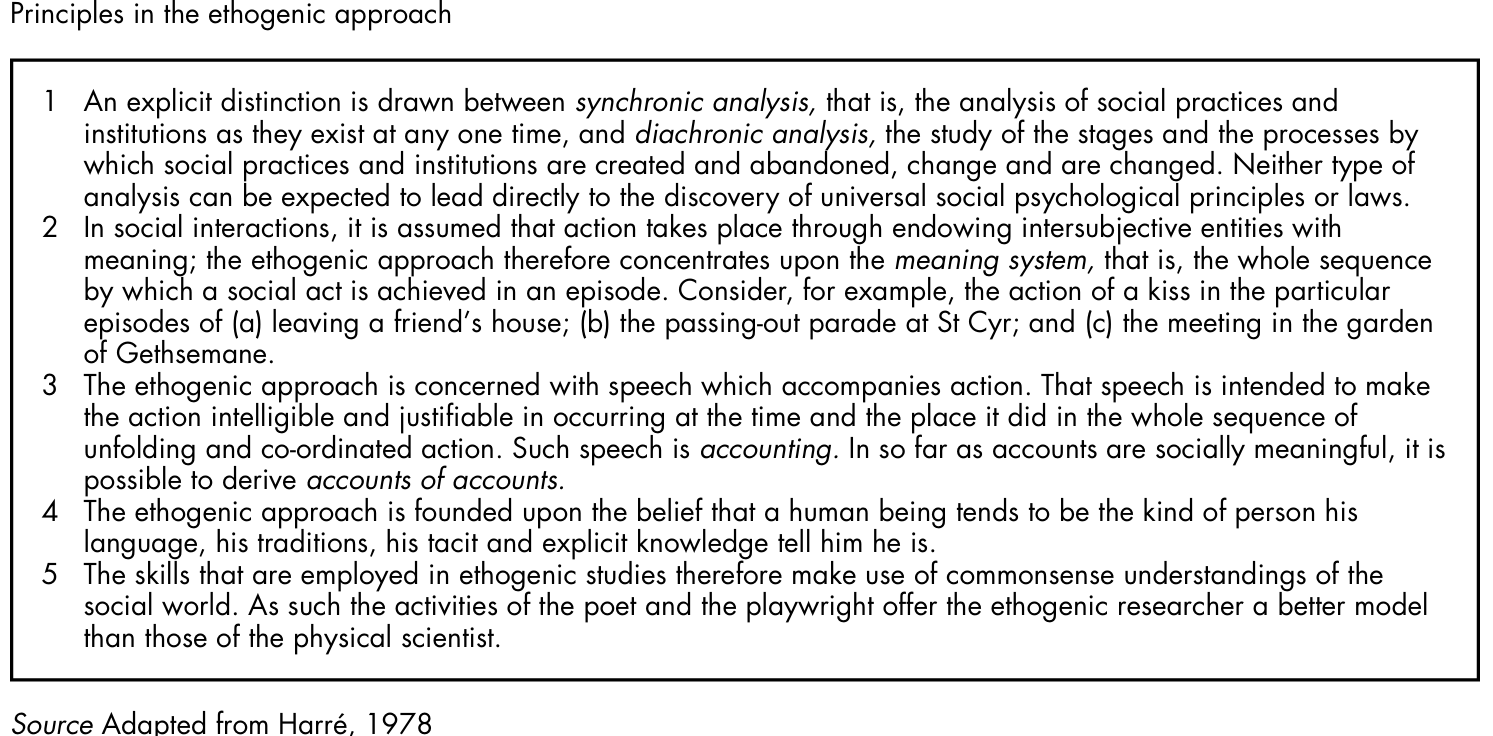

Harré (1978) identifies five main principles in the ethnographic approach. They are set out in Box 1.

Understanding Social Episodes and Their Characteristics

The discussion of accounts and episodes that now follows develops some of the ideas contained in the principles of the ethnographic approach outlined in Box 1. We have already noted that accounts must be seen within the context of social episodes. The idea of an episode is a fairly general one.

What Makes an Episode?

The concept itself may be defined as any coherent fragment of social life. Being a natural division of life, an episode will often have a recognizable beginning and end, and the sequence of actions that constitute it will have some meaning for the participants. Episodes may thus vary in duration and reflect innumerable aspects of life. A pupil entering primary school at seven and leaving at eleven would be an extended episode.

A two-minute television interview with a political celebrity would be another. The con tents of an episode which interest the ethnographic researcher include not only the perceived behavior such as gesture and speech, but also the thoughts, the feelings and the intentions of those taking part. And the ‘speech’ that accounts for those thoughts, feelings and intentions must be conceived of in the widest connotation of the word.

Thus, accounts may be personal records of the events we experience in our day-to-day lives, our conversations with neighbors, our letters to friends, our entries in diaries. Accounts serve to explain our past, present and future oriented actions. Providing that accounts are authentic, it is argued, there is no reason why they should not be used as scientific tools in explaining people’s actions.

How to Collect and Analyze Accounts: Step-by-Step Procedures

The Account-Gathering Method

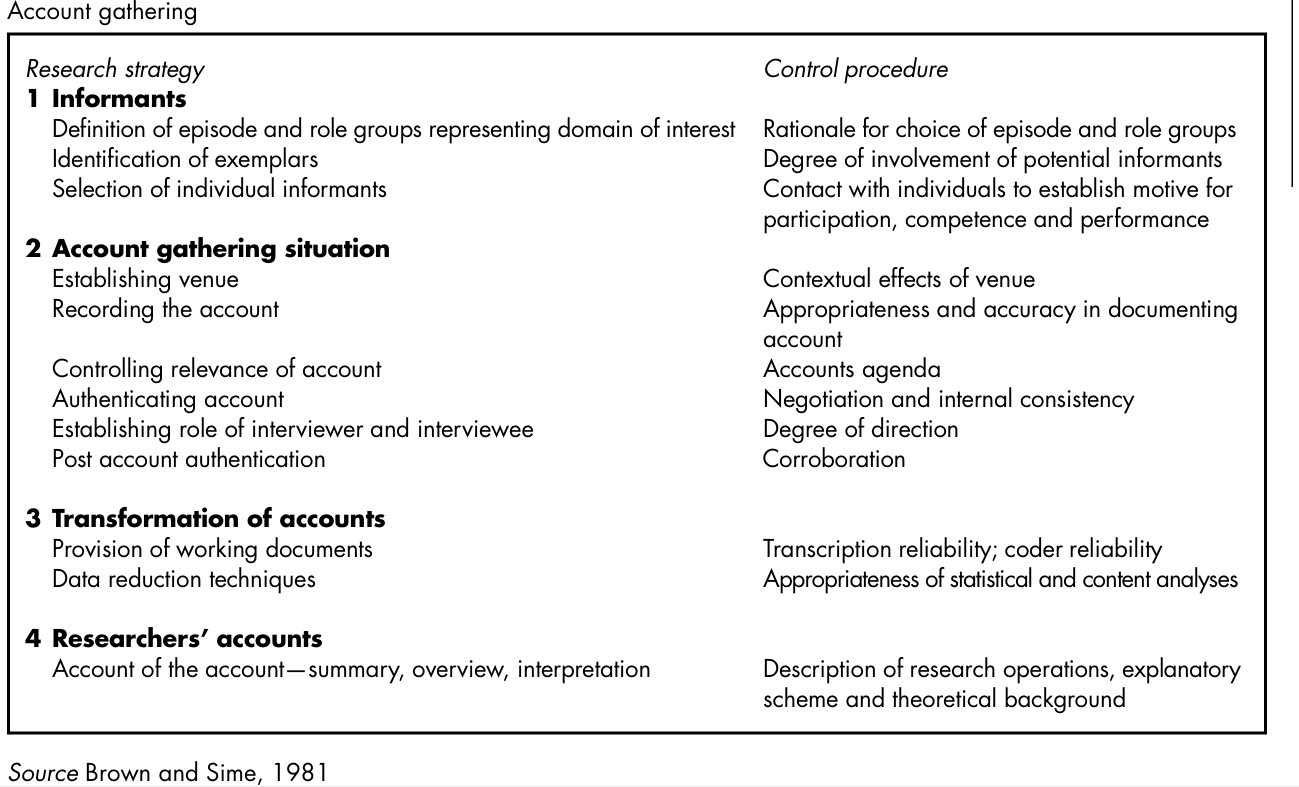

The account-gathering method proposed by Brown and Sime (1977) is summarized in Box 2. It involves attention to informants, the account-gathering situation, the transformation of accounts, and researchers’ accounts, and sets out control procedures for each of these elements.

Problems of eliciting, analyzing and authenticating accounts are further illustrated in the following outlines of two educational studies. The first is concerned with valuing among older boys and girls; the second is to do with the activities of pupils and teachers in using computers in primary classrooms.

Experience-Sampling Technique

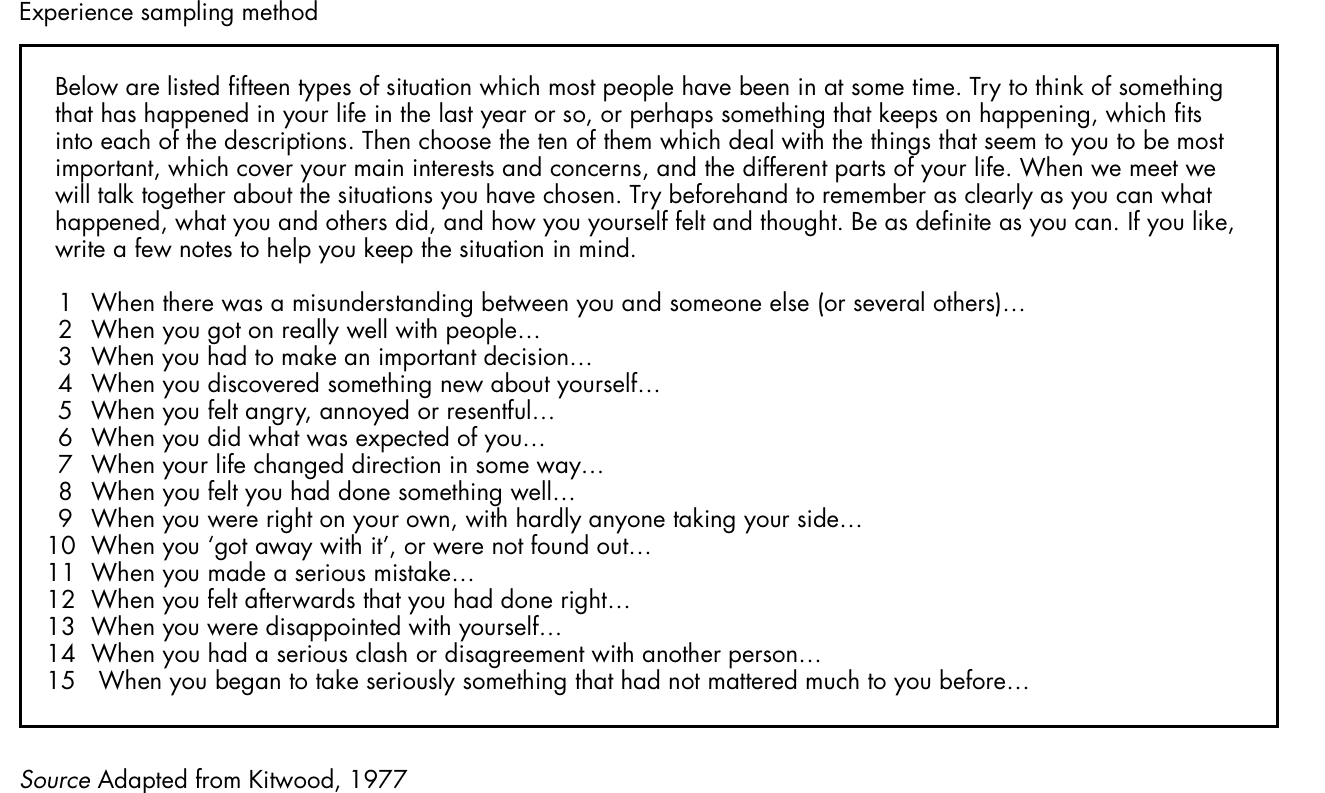

In a study of adolescent values, Kitwood (1977) developed an experience-sampling method, that is, a qualitative technique for gathering and analyzing accounts based upon tape-recorded interviews that were themselves prompted by the fifteen situations listed in Box 3.

Because the experience-sampling method avoids interrogation, the material which emerges is less organized than that obtained from a tightly structured interview. Successful handling of individual accounts therefore requires the re searcher to know the interview content extremely well and to work toward the gradual emergence of tentative interpretive schemata which she then modifies, confirms or falsifies as the research continues.

Eight Methods for Analyzing Recorded Accounts

Kitwood identifies eight methods for dealing with the tape-recorded accounts. Methods 1–4 are fairly close to the approach adopted in handling questionnaires; and methods 5–8 are more in tune with the ethnographic principles that we identified earlier:

1 The total pattern of choice the frequency of choice of various items permits some surface generalizations about the participants, taken as a group. The most revealing analyses may be those of the least and most popular items.

2 Similarities and differences Using the same technique as in method 1, it is possible to investigate similarities and differences within the total sample of accounts according to some characteristic(s) of the participants such as age, sex, level of educational attainment, etc.

3 Grouping items together it may be convenient for some purposes to fuse together categories that cover similar subject matter. For example, items 1, 5 and 14 in Box 3 relate to conflict; items 4, 7 and 15, to personal growth and change.

4 Categorization of content the content of a particular item is inspected for the total sample and an attempt is then made to develop some categories into which all the material will fit. The analysis is most effective when two or more researchers work in collaboration, each initially proposing a category system independently and then exchanging views to negotiate a final category system.

5 Tracing a theme this type of analysis transcends the rather artificial boundaries which the items themselves imply. It aims to collect as much data as possible relevant to a particular topic regardless of where it occurs in the interview material. The method is exacting because it requires very detailed knowledge of content and may entail going through taped interviews several times. Data so collected may be further analyzed along the lines suggested in method 4 above.

6 The study of omissions The researcher may well have expectations about the kind of issues likely to occur in the interviews. When some of these are absent, that fact may be highly significant. The absence of an anticipated topic should be explored to discover the correct explanation of its omission.

7 Reconstruction of a social life-world this method can be applied to the accounts of a number of people who have part of their lives in common, for example, a group of friends who go around together. The aim is to attempt some kind of reconstruction of the world which the participants share in analyzing the fragmentary material obtained in an interview. The researcher seeks to understand the dominant modes of orienting to reality, the conceptions of purpose and the limits to what is perceived.

8 Generating and testing hypotheses New hypotheses may occur to the researcher during the analysis of the tape-recordings. It is possible to do more than simply advance these as a result of tentative impressions; one can loosely apply the hypothetic-deductive method to the data.

This involves putting the hypothesis forward as clearly as possible, working out what the verifiable inferences from it would logically be, and testing these against the account data. Where these data are too fragmentary, the researcher may then consider what kind of evidence and method of obtaining it would be necessary for more thorough hypothesis testing. Subsequent sets of interviews forming part of the same piece of research might then be used to obtain relevant data.

In the light of the weaknesses in account gathering and analysis (discussed later), Kitwood’s suggestions of safeguards are worth mentioning. First, he calls for cross-checking between researchers as a precaution against consistent but unrecognized bias in the interviews themselves. Second, he recommends member tests, that is, taking hypotheses and unresolved problems back to the participants themselves or to people in similar situations to them for their comments.

Only in this way can researchers be sure that they understand the participants’ own grounds for action. Since there is always the possibility that an obliging participant will readily confirm the researcher’s own speculations, every effort should be made to convey to the participant that one wants to know the truth as he or she sees it, and that one is as glad to be proved wrong as right.

A study by Blease and Cohen (1990) used cross-checking as a way of validating the classroom observation records of co-researchers, and member tests to authenticate both quantitative and qualitative data derived from teacher and pupil informants. Thus, in the case of cross checking, the classroom observation schedules of research assistants and researchers were compared and discussed, to arrive at definitive accounts of the range and duration of specific computer activities occurring within observation sessions.

Member tests arose when interpretations of interview data were taken back to participating teachers for their comments. Similarly, pupils’ scores on certain self-concept scales were discussed individually with respondents in or der to ascertain why children awarded themselves high or low marks in respect of a range of skills in using computer program.

Advanced Analysis Techniques for Qualitative Data

Network Analysis: Mapping Complex Relationships

Another technique that has been successfully employed in the analysis of qualitative data is described by its originators as ‘systematic network analysis’ (Bliss, Monk and Ogborn, 1983). Drawing upon developments in artificial intelligence, Bliss and her colleagues employed the concept of ‘relational network’ to represent the content and structuring of a person’s knowledge of a particular domain.

Essentially, network analysis involves the development of an elaborate system of categories by way of classifying qualitative data and preserving the essential complexity and subtlety of the materials under investigation. A notational technique is employed to generate network-like structures that show the inter-dependencies of the categories as they are developed. Network mapping is akin to cognitive mapping,1 an example of which can be seen in the work of Bliss et al. (1983).

Criteria for Effective Networks

Bliss et al. (1983) point out that there cannot be one overall account of criteria for judging the merits of a particular network. They do, however, attempt to identify a number of factors that ought to feature in any discussion of the standards by which a network might fairly be judged as adequate.

First, any system of description needs to be valid and reliable: valid in the sense that it is appropriate in kind and, within that kind, sufficiently complete and faithful; reliable in the sense that there exists an acceptable level of agreement between people as to how to use the network system to describe data.

Second, there are properties that a network description should possess such as clarity, completeness and self-consistency. These relate to a further criterion of ‘network utility’, the sufficiency of detail contained in a particular network.

A third property that a network should possess is termed ‘learnability’. Communicating the terms of the analysis to others, say the authors, is of central importance. It follows therefore that much hinges on whether networks are relatively easy or hard to teach to others. A fourth aspect of network acceptability has to do with its ‘testability’.

Bliss et al. identify two forms of testability, the first having to do with testing a network as a ‘theory’ against data, the second with testing data against a ‘theory’ or expectation via a network. Finally, the terms ‘expressiveness’ and ‘persuasiveness’ refer to qualities of language used in developing the network structure. And here, the authors proffer the following advice.

‘Helpful as the choice of an expressive coding mood or neat use of indentation or brackets may be, the code actually says no more than the network distinguishes’ (our italics). To conclude, network analysis would seem to have a useful role to play in educational research by providing a technique for dealing with the bulk and the complexity of the accounts that are typically generated in qualitative studies.

Discourse Analysis in Educational Research

Discourse researchers explore the organization of ordinary talk and everyday explanations and the social actions performed in them. Collecting, transcribing and analyzing discourse data constitutes a kind of psychological ‘natural history’ of the phenomena in which discourse analysts are interested (Edwards and Potter, 1993).

Discourses can be regarded as sets of linguistic material that are coherent in organization and content and enable people to construct meaning in social contexts (Coyle, 1995:245).

The emphasis on the construction of meaning indicates the action perspective of discourse analysis (ibid.) and this resonates with the notion of speech acts mentioned at the start of this post: locutions, illocutions and per locutions. Further, the focus on discourse and speech acts links this style of research to Habermas’s critical theory set out at the start of this book.

Habermas argues that utterances are never simply sentences (Habermas, 1970:368) that are dis embodied from context, but, rather, their meaning derives from the inter subjective contexts in which they are set.

Understanding Speech Acts and Their Functions

A speech situation has a double structure, the propositional content (the locutionary aspect—what is being said) and the performance based content (the illocutionary and perlocutionary aspect—what is being done or achieved through the utterance). For Habermas (1979, 1984) each utterance has to abide by the criteria of legitimacy, truth, rightness, sincerity and comprehensibility.

His concept of the ‘ideal speech situation’ argues that speech—and, for our purposes here—discourse, should seek to be empowering and not subject to repression or ideological distortion.

His ideal speech situation is governed by several principles, not the least of which are: mutual understanding between participants, freedom to enter a discourse, an equal opportunity to use speech acts, discussion to be free from domination, the movement towards consensus resulting from the discussion alone and the force of the argument alone (rather than the position power of speakers).

For Habermas, then, discourse analysis would seek to uncover, through ideological critique) the repressive forces which ‘systematically distort’ communication. For our purposes, we can take from Habermas the need to expose and interrogate the dominator influences that not only thread through the discourses which re searchers are studying, but the discourses that the research itself produces.

Recent developments in discourse analysis have made important contributions to our understanding of children’s thinking, challenging views (still common in educational circles) of ‘the child as a lone organism, constructing a succession of general models of the world as each new stage is mastered’ (Edwards, 1991). Rather than treating children’s language as representative of an inner cognitive world to be explored experimentally by controlling for a host of intruding variables, discourse analysts treat that language as action, as ‘situated dis cursive practice’.

By way of example, Edwards (1993) explores discourse data emanating from a visit to a greenhouse by 5-year-old pupils and their teacher, to see plants being propagated and grown. His analysis shows how children take understandings of adults’ meanings from the words they hear and the situations in which those words are used. And in turn, adults (in this case, the teacher) take from pupils’ talk, not only what they might mean but also what they could and should mean.

What Edwards describes as ‘the discursive appropriation of ideas’ (Edwards 1991) is illustrated in Box 4. Discourse analysis requires a careful reading and interpretation of textual material, with interpretation being supported by the linguistic evidence. The inferential and interactional aspects of discourse and discourse analysis suggest the need for the researcher to be highly sensitive to the nuances of language (Coyle, 1995:247).

In discourse analysis, as in qualitative data analysis generally (Miles and Huberman, 1984), the researcher can use coding at an early stage of analysis, assigning codes to the textual material being studied (Parker, 1992; Potter and Wetherell, 1987).

This enables the researcher to discover patterns and broad areas in the discourse; computer programs such as Code-A-Text and Ethnographic can assist here. With this achieved the researcher can then re-examine the text to discover intentions, functions and consequences of the discourse (examining the speech act functions of the discourse, e.g. to impart information, to persuade, to accuse, to censure, to encourage etc).

By seeking alternative explanations and the degree of variability in the discourse, it is possible to rule out rival interpretations and arrive at a fair reading of what was actually taking place in the dis course in its social context. The application of discourse analysis to our understanding of classroom learning processes is well exemplified in a study by Edwards and Mercer (1987).

Rather than taking the classroom talk as evidence of children’s thought processes, the researchers explore it as ‘contextualized dialogue with the teacher. The discourse itself is the educational reality and the issue becomes that of examining how teacher and children construct a shared account, a common interpretative frame work for curriculum knowledge and for what happens in the classroom’ (Edwards, 1991).

Overriding asymmetries between teachers and pupils, Edwards concludes, both cognitive (in terms of knowledge) and interactive (in terms of power), impose different discursive patterns and functions. Indeed Edwards (1980) suggests that teachers control classroom talk very effectively, reproducing asymmetries of power in the classroom by telling the students when to talk, what to talk about, and how well they have talked.

Discourse analysis has been criticized for its lack of systematicity (Coyle, 1995:256), for its emphasis on the linguistic construction of a social reality, and the impact of the analysis in shifting attention away from what is being analyzed and towards the analysis itself, i.e. the risk of losing the independence of phenomena. Dis course analysis risks reifying discourse. One must not lose sight of the fact that the discourse analysis itself is a text, a discourse that in turn can be analyzed for its meaning and inferences, rendering the need for reflexivity to be high (Ashmore, 1989).

Analyzing Classroom Dialogue

Edwards and Westgate (1987) show what substantial strides have been made in recent years in the development of approaches to the investigation of classroom dialogue. Some methods encourage participants to talk; others wait for talk to emerge and sophisticated audio/video techniques record the result by whatever method it is achieved.

Thus captured, dialogue is re viewed, discussed and reflected upon; moreover, that reviewing, discussing and reflecting is usually undertaken by researchers. It is they, generally, who read ‘between the lines’ and ‘within the gaps’ of classroom talk by way of interpreting the intentionality of the participating discussants.

Analyzing Social Episodes

A major problem in the investigation of that natural unit of social behavior, the ‘social episode’, has been the ambiguity that surrounds the concept itself and the lack of an acceptable taxonomy by which to classify an interaction sequence on the basis of empirically quantifiable characteristics. Several quantitative studies have been undertaken in this field.

For example Magnusson (1971), Ekehammer and Magnusson (1973) and McQuitty (1957) use factor analysis and linkage analysis respectively, whilst Forgas (1976, 1978), Peevers and Secord (1973) and Secord and Peevers (1974) use multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis.

Real-World Application: Case Studies

The ‘free commentary’ method that Secord and Peevers (1974) recommend as a way of probing for explanations of people’s behavior lies at the very heart of the ethnographer’s skills. In the example of ethnographic research that follows, one can detect the researcher’s attempts to get below the surface data and to search for the deeper, hidden patterns that are only revealed when attention is directed to the ways that group members interpret the flow of events in their lives.

Heath’s Study on Classroom Communication

Heath: ‘Questioning at home and at school’ (1982)

Heath’s study of misunderstandings existing between black children and their white teachers in classrooms in the south of the United States brought to light teachers’ assumptions that pupils would respond to language routines and the uses of language in building knowledge and skills just as other children (including their own) did (Heath, 1982).5 Specifically, she sought to understand why these particular children did not respond just as others did.

Her research involved eliciting explanations from both the children’s parents and teachers. ‘We don’t talk to our children like you folks do’, the parents observed when questioned about their children’s behavior. Those children, it seemed to Heath, were not regarded as information givers or as appropriate conversational partners for adults. That is not to say that the children were excluded from language participation.

They did, in fact, participate in a language that Heath describes as rich in styles, speakers and topics. Rather, it seemed to the researcher that the teachers’ characteristic mode of questioning was ‘to pull at tributes of things out of context, particularly out of the context of books and name them—queens, elves, police, red apples’ (Heath, 1982).

The parents did not ask these kinds of questions of their children, and the children themselves had their own ways of deflecting such questions, as the example in Box 5 well illustrates. Heath elicited both parents’ and teachers’ accounts of the children’s behavior and their apparent communication ‘problems’ (see Box 6). Her account of accounts arose out of periods of participation and observation in class rooms and in some of the teachers’ homes.

In particular, she focused upon the ways in which ‘the children learned to use language to satisfy their needs, ask questions, transmit information, and convince those around them that they were competent communicators’ (Heath, 1982). This involved her in a much wider and more intensive study of the total fabric of life in Trackton, the southern community in which the research was located.

Over five years… I was able to collect data across a wide range of situations and to follow some children longitudinally as they acquired communicative competence in Trackton. Likewise, at various periods during these years, I observed Trackton adults in public service encounters and on their jobs…

The context of language use, including setting, topic, and participants (both those directly involved in the talk and those who only listened) determined in large part how community members, teachers, public service personnel, and fellow workers judged the communicative competence of Trackton residents. (Heath, 1982)

Challenges and Limitations of Account-Based Research

The importance of the meaning of events and actions to those who are involved in them is now generally recognized in social research. The implications of the ethnographic stance in terms of actual research techniques, however, remain problematic.

The Issue of Multiple Meanings

Menzel (1978)7 discusses a number of ambiguities and shortcomings in the ethnographic approach, arising out of the multiplicity of meanings that may be held for the same behavior. Most behavior, Menzel observes, can be as signed meanings and more than one of these may very well be valid simultaneously. It is fallacious therefore, he argues, to insist upon determining ‘the’ meaning of an act.

Nor can it be said that the task of interpreting an act is done when one has identified one meaning of it, or the one meaning that the researcher is pleased to designate as the true one. A second problem that Menzel raises is to do with actors’ meanings as sources of bias.

How central a place, he asks, ought to be given to actors’ meanings in formulating explanations of events? Should the researcher exclusively and invariably be guided by these considerations? To do so would be to ignore a whole range of potential explanations which few researchers would wish to see excluded from consideration.

These are far-reaching, difficult issues though by no means intractable. What solutions does Menzel propose? First we must specify ‘to whom’ when asking what acts and situations mean. Second, researchers must make choices and take responsibility in the assignment of meanings to acts; moreover, problem formulations must respect the meaning of the act to us, the researchers. And third, explanations should respect the meanings of acts to the actors themselves but need not invariably be centered on these meanings.

Balancing Insider and Outsider Perspectives

Menzel’s plea is for the usefulness of an outside observer’s accounts of a social episode alongside the explanations that participants themselves may give of that event. A similar argument is implicit in McIntyre and McLeod’s (1978) justification of objective, systematic observation in classroom settings. Their case is set out in Box 7.

Why Use the Ethnographic Approach? Key Strengths

The advantages of the ethnographic approach to the educational researcher lie in the distinctive insights that are made available to her through the analysis of accounts of social episodes. There is a good deal of truth in the assertion of the estrogenically oriented researcher that approaches employ survey techniques such as the questionnaire take for granted the very things that should be treated as problematic in an educational study.

Too often, the phenomena that ought to be the focus of attention are taken as given, that is, they are treated as the starting point of the research rather than becoming the center of the researcher’s interest and effort to discover how the phenomena arose or came to be important in the first place.

Numerous educational studies, for example, have identified the incidence and the duration of disciplinary infractions in school; only relatively recently, however, has the meaning of classroom disorder, as opposed to its frequency and type, been subjected to intensive investigation.

Un like the survey, which is a cross-sectional technique that takes its data at a single point in time, the ethnographic study employs an ongoing observational approach that focuses upon processes rather than products. Thus it is the process of becoming deviant in school which would capture the attention of the ethnographic researcher rather than the frequency and type of misbehavior among k types of ability in children located in n kinds of school.

Stories and Storytelling as Research Data

A comparatively neglected area in educational research is the field of stories and storytelling. Bauman (1986:3) suggests that stories are oral literature whose meanings, forms and functions are situational rooted in cultural contexts, scenes and events which give meaning to action.

This recalls Bruner (1986) who, echoing the interpretive mode of educational research, regards much action as ‘storied text’, with actors making meaning of their situations through narrative. Stories have a legitimate place as an inquiry method in educational research (Parsons and Lyons, 1979), and, indeed, Jones (1990), Crow (1992), Dunning (1993) and Thody (1997) place them on a par with interviews as sources of evidence for research.

Thody (1997:331) suggests that, as an extension to interviews, stories—like biographies—are rich in authentic, live data; they are, she avers, an ‘unparalleled method of reaching practitioners’ mindsets’. She provides a fascinating report on stories as data sources for educational management research as well as for gathering data from young children (pp. 333–4).

How to Analyze Stories in Research

Thody indicates (p. 331) how stories can be analyzed, using, for example, conventional techniques such as: categorizing and coding of content; thematization; concept building. In this respect stories have their place alongside other sources of primary and secondary documentary evidence (e.g. case studies, biographies).

They can be used in export facto research, historical research, as accounts or in action research; in short they are part of the everyday battery of research instruments that are available to the researcher. The rise in the use of oral history as a legitimate research technique in social research can be seen here to apply to educational research.

Though they might be problematic in that verification is difficult (unless other people were present to verify events reported), stories, being rich in the subjective involvement of the storyteller, offer an opportunity for the researcher to gather authentic, rich and ‘respectable’ data (Bauman, 1986).

FAQs – Qualitative Research Accounts and Storytelling (Ethnographic Approach)

1. What is storytelling in qualitative research?

Storytelling in qualitative research is a method of presenting participants’ experiences through narratives. It helps researchers capture context, emotions, and meanings that numbers alone cannot represent.

2. How does ethnography differ from other qualitative approaches?

Ethnography focuses on understanding people’s behaviors, beliefs, and interactions within their natural settings—often through prolonged observation, participation, and interviews—whereas other approaches may rely more on structured data collection.

3. Why are narratives important in ethnographic studies?

Narratives provide depth and authenticity. They allow researchers to interpret social realities and cultural meanings as lived by participants, helping readers connect emotionally and intellectually with the findings.

4. What are researcher field notes in ethnographic storytelling?

Field notes are detailed written records of observations, conversations, and reflections made by the researcher in the field. They are vital for reconstructing events, analyzing context, and building credible ethnographic stories.

5. How is validity maintained in qualitative storytelling research?

Validity is achieved through triangulation, member checking, reflexivity, and thick description—ensuring that the researcher’s interpretations align with participants’ realities and that findings are trustworthy.

6. What ethical issues arise in ethnographic research?

Ethical concerns include informed consent, privacy protection, cultural sensitivity, and avoiding misrepresentation of participants’ voices in published accounts.

7. How are ethnographic findings presented in research reports?

Findings are often shared as narratives, case studies, or thematic stories supported by direct quotes, context explanations, and cultural interpretations that reflect participants’ perspectives.

8. Can storytelling be used alongside quantitative data?

Yes. Mixed-methods research often integrates storytelling with quantitative data to provide both statistical trends and rich personal experiences, offering a holistic view of a phenomenon.

Read More:

https://nurseseducator.com/didactic-and-dialectic-teaching-rationale-for-team-based-learning/

https://nurseseducator.com/high-fidelity-simulation-use-in-nursing-education/

First NCLEX Exam Center In Pakistan From Lahore (Mall of Lahore) to the Global Nursing

Categories of Journals: W, X, Y and Z Category Journal In Nursing Education

AI in Healthcare Content Creation: A Double-Edged Sword and Scary

Social Links:

https://www.facebook.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.instagram.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.pinterest.com/NursesEducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/nurseseducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/nurseseducator/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Afza-Lal-Din

https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=F0XY9vQAAAAJ

1 thought on “Qualitative Research Accounts and Storytelling: Complete Guide to the Ethnographic Approach”