The Assessment Reliability Factors and Methods of Measurement for Qualities of Effective Assessment Procedures. Common assessment methods can be divided into two main categories: formative assessments, which are conducted regularly, at least in each class, and summative assessments, which may be conducted after a specific period, such as after a class or a semester.

The Assessment Reliability Factors and Methods of Measurement for Qualities of Effective Assessment Procedures

Score reliability, a crucial aspect of effective assessment, ensures consistent and reliable results over time and across different assessors or test versions. Reliability is influenced by various factors, and there are several methods for measuring and improving it.

Four important methods for assessing reliability are test-retest, parallel testing, internal consistency, and inter-rater reliability. In theory, reliability refers to the actual deviation of the score from the observed deviation. Reliability is primarily an empirical question that focuses on the performance of an empirical measure.

A measure has high reliability if it produces similar results under consistent conditions: it is the property of a set of test results that refers to the proportion of random errors from the measurement process that can be included in the results.

What is Assessment Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency of scores. If an assessment produces reliable scores, the same group of students would achieve approximately the same scores if the same assessment were given on another occasion. Each assessment produces a limited measure of performance at a specific time. If this measurement is reasonably consistent over time, with different rates, or with different samples of the same domain, teachers can be more confident in the assessment results.

Factors Affecting Results

However, assessment results cannot be perfectly consistent because many extraneous factors may influence the measurement of performance. Scores may be consistent because:

- The behavior being measured is unstable over time because of fluctuations in memory, attention, and effort; intervening learning experiences; or varying emotional or health status.

- The sample of tasks varies from one assessment to another, and some students find one assessment to be easier than the other because it contains tasks related to topics they know well.

- Assessment conditions vary significantly between assessments; or

- Scoring procedures are inconsistent (the same rater may use different criteria on different assessments, or different raters may not reach perfect agreement on the same assessment). These and other factors introduce a certain but unknown amount of error into every measurement.

Methods to Measure Reliability

Methods of determining assessment reliability, therefore, are a means of estimating how many measurement error is present under varying assessment conditions. When assessment results are reasonably consistent, there is less measurement error and greater reliability (Miller et al., 2009). For purposes of understanding sources of inconsistency, it is helpful to view an assessment score as having two components, a true score and an error score, represented by the following equation:

X=T+E [Equation 2.1]

A student’s current assessment score (X) is also known as the observed or obtained score. That student’s hypothetical true score (T) cannot be measured directly because it is the average of all scores the student would obtain if tested on many occasions with the same test. The observed score contains a certain amount of measurement error (E), which may be a positive or a negative value.

This error of measurement, representing the difference between the observed score and the true score, results in a student’s obtained score being higher or lower than his or her true score ( Nitko & Brookhart, 2007). If it were possible to measure directly the amount of measurement error that occurred on each testing occasion, two of the values in this equation would be known (X and E), and we would be able to calculate the true score (T).

However, we can only estimate indirectly the amount of measurement error, leaving us with a hypothetical true score. Therefore, teachers need to recognize that the score obtained on any test is only an estimate of what the student really knows about the domain being tested.

For example, Matt may obtain a higher score than Kelly on a community health nursing unit test because Matt truly knows more about the content than Kelly does. Test scores should reflect this kind of difference, and if the difference in knowledge is the only explanation for the score difference, no error is involved.

However, there may be other potential explanations for the difference between Kelly’s and Matt’s test scores. Matt may have behaved dishonestly to obtain a copy of the test in advance; Knowing which items would be included, he had the opportunity to use unauthorized resources to determine the correct answers to those items. In his case, measurement error would have increased Matt’s obtained score.

Kelly may have worked overtime the night before the test and may not have gotten enough sleep to allow her to feel alert during the test. Thus, her performance may have been affected by her fatigue and her decreased ability to concentrate, resulting in an obtained score lower than her true score. One goal of assessment designers therefore is to maximize the amount of score variance that explains real differences in ability and to minimize the amount of random error variance of scores.

More About Assessment Reliability

The following points further explain the concept of assessment reliability (Miller et al., 2009):

- Reliability pertains to assessment results, not to the assessment instrument itself. The reliability of results produced by a given instrument will vary depending on the characteristics of the students being assessed and the circumstances under which it is used. Reliability should be estimated with each use of the assessment instrument.

- A reliability estimate always refers to a particular type of consistency. Assessment results may be consistent over different periods of time, or different samples of the domain, or different raters or observers.

It is possible for assessment results to be reliable in one or more of these respects but not in others. The desired type of reliability evidence depends on the intended use of the assessment results.

For example, if the faculty wants to assess students’ ability to make sound clinical decisions in a variety of settings, a measure of consistency over time would not be appropriate. Instead, an estimate of consistency of performance across different tasks would be more useful.

- A reliability estimate is always calculated with statistical indices. Consistency of assessment scores over time, among raters, or across different assessment measures involves determining the relationship between two or more sets of scores. The extent of consistency is expressed in terms of a reliability coefficient (a form of correlation coefficient) or a standard error of measurement.

A reliability coefficient differs from a validity coefficient (described earlier) in that it is based on agreement between two sets of assessment results from the same procedure instead of agreement with an external criterion.

- Reliability is an essential but insufficient condition for validity. Teachers cannot make valid inferences from inconsistent assessment results. Conversely, highly consistent results may indicate only that the assessment measured the wrong construct (although doing it very reliably).

Thus, low reliability always produces a low degree of validity, but a high reliability estimate does not guarantee a high degree of validity. “In short, reliability merely provides the consistency that makes validity possible” (Miller et al., 2009, p. 108) an example may help to illustrate the relationship between validity and reliability. Suppose that the author of this chapter was given a test of his knowledge of assessment principles.

The author of a textbook on assessment in nursing education might be expected to achieve a high score on such a test. However, if the test were written in Mandarin Chinese, the author’s score might be very low, even if she were a remarkably good guesser, because she cannot read Mandarin Chinese. If the same test were administered the following week, and every week for a month, her scores would likely be consistently low.

Therefore, these test scores would be considered reliable because there would be a high correlation between scores obtained on the same test over a period of several administrations. But a valid score-based interpretation of the author’s knowledge of assessment principles could not be drawn because the test was not appropriate for its intended use.

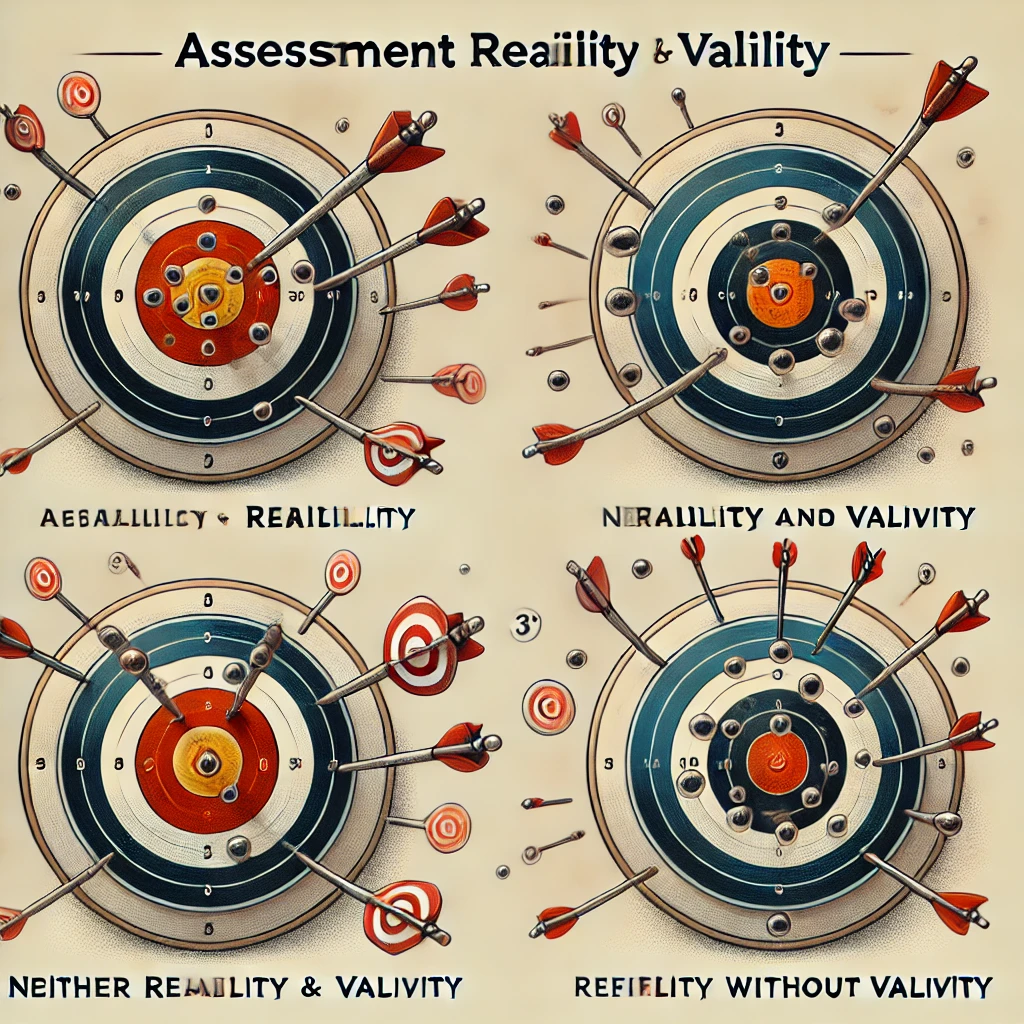

Figure uses a target-shooting analogy to further illustrate these relationships. When they design and administer assessments, teachers attempt to consistently (reliably) measure the true value of what students know and can do (hit the bull’s eye); if they succeed, they can make valid inferences from assessment results.

Target 1 illustrates the reliability of scores that are closely grouped on the bull’s eye, the true score, allowing the teacher to make valid inferences about them. Target 2 displays assessment scores that are widely scattered at a distance from the true score; these scores are not reliable, contributing to a lack of validity evidence.

Target 3 shows assessment scores that are reliable because they are closely grouped together, but they are still distant from the true score. The teacher would not be able to make valid interpretations of such scores (Miller et al., 2009).

Read More:

https://nurseseducator.com/didactic-and-dialectic-teaching-rationale-for-team-based-learning/

https://nurseseducator.com/high-fidelity-simulation-use-in-nursing-education/

First NCLEX Exam Center In Pakistan From Lahore (Mall of Lahore) to the Global Nursing

Categories of Journals: W, X, Y and Z Category Journal In Nursing Education

AI in Healthcare Content Creation: A Double-Edged Sword and Scary

Social Links:

https://www.facebook.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.instagram.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.pinterest.com/NursesEducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/nurseseducator/

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Afza-Lal-Din

https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=F0XY9vQAAAAJ