Let Explore Understanding Personal Construct Theory: A Complete Guide to Repertory Grid Technique in Educational Research. The book “Understanding Personal Construct Theory: A Complete Guide to the Repertory Grid Technique in Educational Research” appears to be a conceptual or potential publication, as the research did not reveal any concrete information about a previously published book with exactly this title, author, or publication date.

A Complete Guide to Repertory Grid Technique in Educational Research: Understanding Personal Construct Theory

Introduction to Personal Construct Theory

The Origins: George Kelly’s Revolutionary Approach

One of the most interesting theories of personality to have emerged this century and one that has had an increasing impact on educational research is ‘personal construct theory’.

Understanding Personal Constructs

Personal constructs are the basic units of analysis in a complete and formally stated theory of personality proposed by George Kelly in a book entitled The Psychology of Personal Constructs (1955). Kelly’s own experiences were intimately related to the development of his imaginative theory. He began his career as a school psychologist dealing with problem children referred to him by teachers. As his experiences widened, instead of merely corroborating a teacher’s com plaint about a pupil, Kelly tried to understand the complaint in the way the teacher construed it.

This change of perspective constituted a significant reformulation of the problem. In practical terms it resulted in an analysis of the teacher making the complaint as well as the problem pupil. By viewing the problem from a wider perspective Kelly was able to envisage a wider range of solutions. The insights George Kelly gained from his clinical work led him to the view that there is no objective, absolute truth and that events are only meaningful in relation to the ways that are construed by individuals.

Kelly’s primary focus is upon the way individuals perceive their environment, the way they interpret what they perceive in terms of their existing mental structure, and the way in which, as a consequence, they behave towards it. In The Psychology of Personal Constructs, Kelly proposes a view of people actively engaged in making sense of and ex tending their experience of the world. Personal constructs are the dimensions that we use to conceptualize aspects of our day-to-day world.

The Role of the Individual as Scientist

The constructs that we create are used by us to forecast events and rehearse situations before their actual occurrence. According to Kelly, we take on the role of scientist seeking to predict and control the course of events in which we are caught up. For Kelly, the ultimate explanation of human behaviour ‘lies in scanning man’s undertakings, the questions he asks, the lines of inquiry he initiates and the strategies he employs’ (Kelly, 1969).

Education, in Kelly’s view, is necessarily experimental. Its ultimate goal is individual fulfillment and the maximizing of individual potential. In emphasizing the need of each individual to question and explore, construct theory implies a view of education that capitalizes upon the child’s natural motivation to engage in spontaneous learning activities. It follows that the teacher’s task is to facilitate children’s ongoing exploration of the world rather than impose adult perspectives upon them.

Kelly’s ideas have much in common with those to be found in Rousseau’s Emile. The central tenets of Kelly’s theory are set out in terms of a fundamental postulate and a number of corollaries. It is not proposed here to undertake a detailed discussion of his theoretical propositions. Good commentaries are available in Bannister (1970) and Ryle (1975). Instead, we look at the method suggested by Kelly of eliciting constructs and assessing the mathematical relationships between them, that is, repertory grid technique.

The Fundamentals of Repertory Grid Technique

Key Characteristics: Elements and Constructs

Kelly proposes that each person has access to a limited number of ‘constructs’ by means of which she evaluates the phenomena that constitute her world. These phenomena—people, events, objects, ideas, institutions and so on—are known as ‘elements’.

The Bi-Polar Nature of Constructs

He further suggests that the constructs that each of us employs may be thought of as bi-polar, that is, capable of being defined in terms of polar adjectives (good-bad) or polar phrases (makes me feel happy-makes me feel sad). A number of different forms of repertory grid technique have been developed since Kelly’s first formulation.

Flexibility and Adaptability in Research

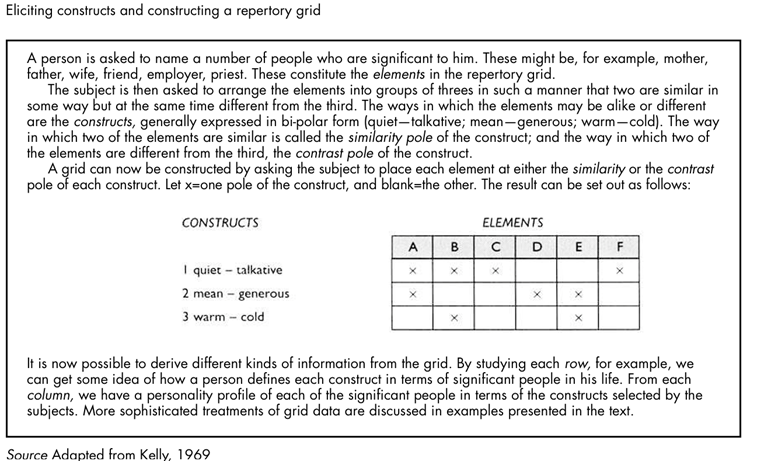

All have the two essential characteristics in common that we have already identified, that is, constructs—the dimensions used by a person in conceptualizing aspects of her world; and elements—the stimulus objects that a person evaluates in terms of the constructs she employs. In Data 19.1, we illustrate the empirical technique suggested by Kelly for eliciting constructs and identifying their relationship with elements in the form of a repertory grid.

Since Kelly’s original account of what he called ‘The Role Construct Repertory Grid Test ‘several variations of repertory grid have been developed and used in different areas of research. It is the flexibility and adaptability of repertory grid technique that has made it such an attractive tool to researchers in psychiatric, counseling, and more recently, educational set tings.

We now review a number of developments in the form and the use of the technique. Alban Metcalf (1997:318) suggests that the use of repertory grids is largely twofold: in their ‘static’ form they elicit perceptions that people hold of others at a single point in time; in their ‘dynamic’ form, repeated application of the method indicates changes in perception over time; the latter is useful for charting development and change.

Methodological Approaches

Elicited vs. Provided Constructs

A central assumption of this ‘standard’ form of repertory grid is that it enables the researcher to elicit constructs that subjects customarily use in

interpreting and predicting the behaviour of those people who are important in their lives. Kelly’s method of eliciting personal constructs required the subject to complete a number of cards, ‘each showing the name of a person in [his/her] life’.

Similarly, in identifying elements, the subject was asked, ‘Is there an important way in which two of [the elements]—any two— differ from the third?’, i.e. triadic elicitation (see, for example, Nash, 1976).

This insistence upon important persons and important ways that they are alike or differ, where both constructs and elements are nominated by the subjects themselves, is central to Personal Construct Theory. Kelly gives it precise expression in his Individuality Corollary—‘Persons differ from each other in their construction of events.’ Several forms of repertory grid technique now in common use represent a significant departure from Kelly’s individuality corollary in that they provide constructs to subjects rather than elicit constructs from them.

One justification for the use of provided constructs is implicit in Ryle’s commentary on the individuality corollary: ‘Kelly paid rather little attention to developmental and social processes’, Ryle observes, ‘his own concern was with the personal and not the social’. Ryle believes that the individuality corollary would be strengthened by the additional statement that ‘persons resemble each other in their construction of events’ (Ryle, 1975). Can the practice of providing constructs to subjects be reconciled with the individuality corollary assumptions?

A review of a substantial body of research suggests a qualified ‘yes’: [While] it seems clear in the light of research that individuals prefer to use their own elicited constructs rather than provided dimensions to describe themselves and others…the results of several studies suggest that normal subjects, at least, exhibit approximately the same degree of differentiation in using carefully selected supplied lists of adjectives as when they employ their own elicited personal constructs. (Adams-Webber, 1970).

However, see Fransella and Bannister (1977) on elicited versus supplied constructs as a ‘grid-generated’ problem. Bannister and Mair (1968) support the use of supplied constructs in experiments where hypotheses have been formulated and in those involving group comparisons.

The use of elicited constructs alongside supplied ones can serve as a useful check on the meaningfulness of those that are provided, substantially lower inter-correlations between elicited and supplied constructs suggesting, perhaps, the lack of relevance of those provided by the researcher. The danger with supplied constructs, Bannister and Mair argue, is that the researcher may assume that the polar adjectives or phrases she provides are the verbal equivalents of the psychological dimensions in which she is interested.

Methods for Allocating Elements to Constructs

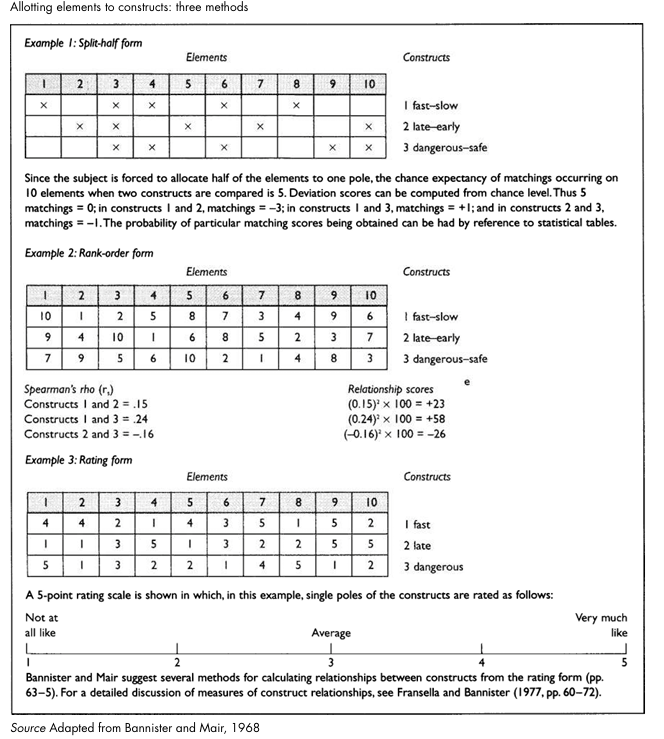

Allotting elements to constructs.When a subject is allowed to classify as many or as few elements at the similarity or the contrast pole, the result is often a very lopsided construct with consequent dangers of distortion in the estimation of construct relationships. Bannister and Mair (1968) suggest two methods for dealing with this problem which we illustrate in Data 19.2.

Split-Half Form

The first, the ‘split-half form’, requires the subject to place half the elements at the similarity pole of each construct, by instructing her to decide which element most markedly shows the characteristics specified by each of the constructs. Those elements that are left are allocated to the contrast pole. As Bannister observes, this technique may result in the discarding of constructs (for example, male-female) which cannot be summarily allocated.

A second method, the ‘rank order form’, as its name suggests, requires the subject to rank the elements from the one which most markedly exhibits the particular characteristic (shown by the similarity pole description) to the one which least exhibits it. As the second example in Data 19.2 shows, a rank order correlation co-efficient can be used to estimate the extent to which there is similarity in the allotment of elements on any two constructs.

Following Bannister, a ‘construct relationship’ is used as scores.) The construct relationship score can be calculated by squaring the correlate score gives an estimate of the percentage variation co-efficient and multiplying by 100. (Because ace that the two constructs share in common in correlations are not linearly related they cannot terms of the rankings on the two grids.

Rating Form

A third method of allotting elements is the ‘rating form’. Here, the subject is required to judge each element on a 7-point or a 5-point scale, for example, absolutely beautiful (7) to absolutely ugly (1). Commenting on the advantages of the rating form, Bannister and Mair (1968) note that it offers the subject greater latitude in distinguishing between elements than that provided for in the original form proposed by Kelly. At the same time the degree of differentiation asked of the subject may not be as great as that demanded in the ranking method. As with the rank order method, the rating form approach also allows the use of most correlation techniques.

The rating form is the third example illustrated in Data 19.2. Alban-Metcalf (1997:317) suggests that there are two principles that govern the selection of elements in the repertory grid technique. The first is that the elements must be relevant to that part of the construct system that is being investigated, and the second is that the selected elements must be representative. The greater the number of elements (typically between 10 and 25) or constructs that are elicited, the greater is the chance of representativeness. Constructs can be psychological (e.g. anxious), physical (e.g. tall), situational (e.g. from this neighborhood), and behavioral (e.g. is good at sport).

Advanced Techniques: Laddering and Pyramid Constructions

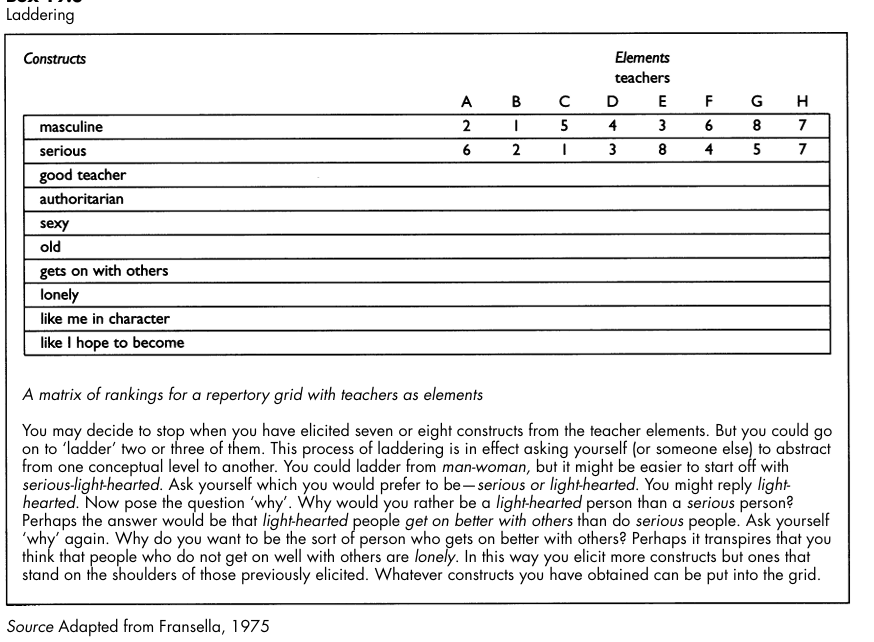

The technique known as laddering arises out of Hinkle’s (1965) important revision of the theory of personal constructs and the method employed in his research. Hinkle’s concern was for the location of any construct within an individual’s construct system, arguing that a construct has differential implications within a given hierarchical context. Here a construct is selected by the interviewer, and the respondent is asked which pole applies to a particular, given element (Alban-Metcalf, 1997:316).

The constructs that are elicited are a sequence that has a logic for the individual and that can be arranged in a hierarchical manner of subordinate and superordinate constructs (ibid.: 317). That is ‘laddering up’, where there is a progression from subordinate to superordinate constructs. The reverse process (superordinate to subordinate) is ‘laddering down’, asking, for example, how the respondent knows that such and such a construct applies to a particular person. Hinkle (1965) went on to develop an Implication Grid or Impgrid, in which the subject is required to compare each of his constructs with every other to see which implies the other.

The question ‘why?’ is asked over and over again to identify the position of any construct in an individual’s hierarchical construct system. Data 19.3 illustrates Hinkle’s laddering technique with an example from educational research reported by Fransella (1975). In pyramid construction respondents are asked to think of a particular ‘element’, a person, and then to specify an attribute which is characteristic of that person. Then the respondent is asked to identify a person who displays the opposite characteristic. This sets out the two poles of the construct. Finally, laddering down of each of the opposite poles is undertaken, thereby constructing a pyramid of relationships between the constructs (Alban-Metcalf, 1997:317)

Administering and Analyzing Repertory Grids

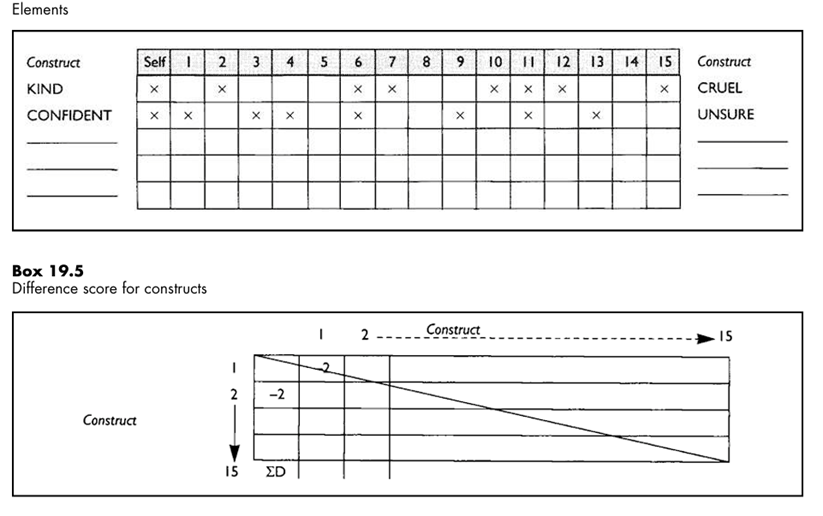

The example of grid administration and analysis outlined below employs the split-half method of allocating elements to constructs and a form of ‘anchor analysis’ devised by Bannister. We assume that 16 elements and 15 constructs have already been elicited by means of a technique such as the one illustrated in Data 19.1.

Step-by-Step Grid Administration

Draw up a grid measuring 16 (elements) by 15 (constructs) as in Data 19.1, writing along the top the names of the elements, but first inserting the additional element, ‘self’. Alongside the rows write in the construct poles. You now have a grid in which each intersection or cell is defined by a particular column.

(element) and a particular row (construct).

The administration takes the form of allocating every element on every construct. If, for example, your first construct is ‘kind—cruel’, allocate each element in turn on that dimension, putting a cross in the appropriate box if you consider that per son (element) kind, or leaving it blank if you consider that person cruel. Make sure that half of the elements are designated kind and half cruel.

Proceed in this way for each construct in turn, always placing a cross where the construct pole to the left of the grid applies, and leaving it blank if the construct pole to the right is applicable. Every element must be allocated in this way, and half of the elements must always be allocated to the left-hand pole.

Analyzing Grid Data

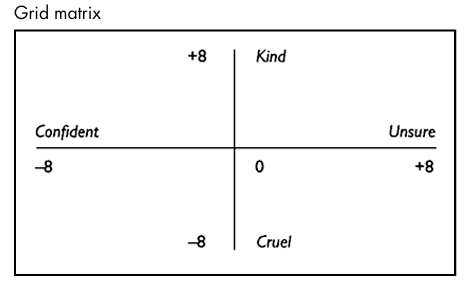

The grid may be regarded as a reflection of conceptual structure in which constructs are linked by virtue of their being applied to the same per sons (elements). This linkage is measured by a process of matching construct rows. To estimate the linkage between constructs 1 and 2 in Data 19.4, for example, count the number of matches between corresponding boxes in each row. A match is counted where the same element has been designated with a cross (or a blank) on both constructs. So, for constructs 1 and 2 in Data 19.4, we count 6 such matches.

By chance we would expect 8 (out of 16) matches, and we may subtract this from the observed value to arrive at an estimate of such deviation from chance.

By matching construct 1 against all remaining constructs (3…15), we get a score for each comparison. Beginning then with construct 2, and comparing this with every other construct (3…15), and so on, every construct on the grid is matched with every other one and a difference score for each obtained. This is recorded in matrix form, with the reflected half of the table also filled in (see difference score for constructs 1–2 in Data 19.5).

The sign of the difference score is retained. It indicates the direction of the linkage. A positive sign show that the constructs are positively associated a negative sign that they are negatively associated. Now add up (without noting sign) the sum of the difference scores for each column (construct) in the matrix.

The construct with the largest difference score is the one which, statistically, accounts for the greatest amount of variance in the grid. Note this down. Now look in the body of the matrix for that construct which has the largest non-significant association with the one which you have just noted (in the case of a 16 element grid as in Data 19.4, this will be a difference score of±3 or less).

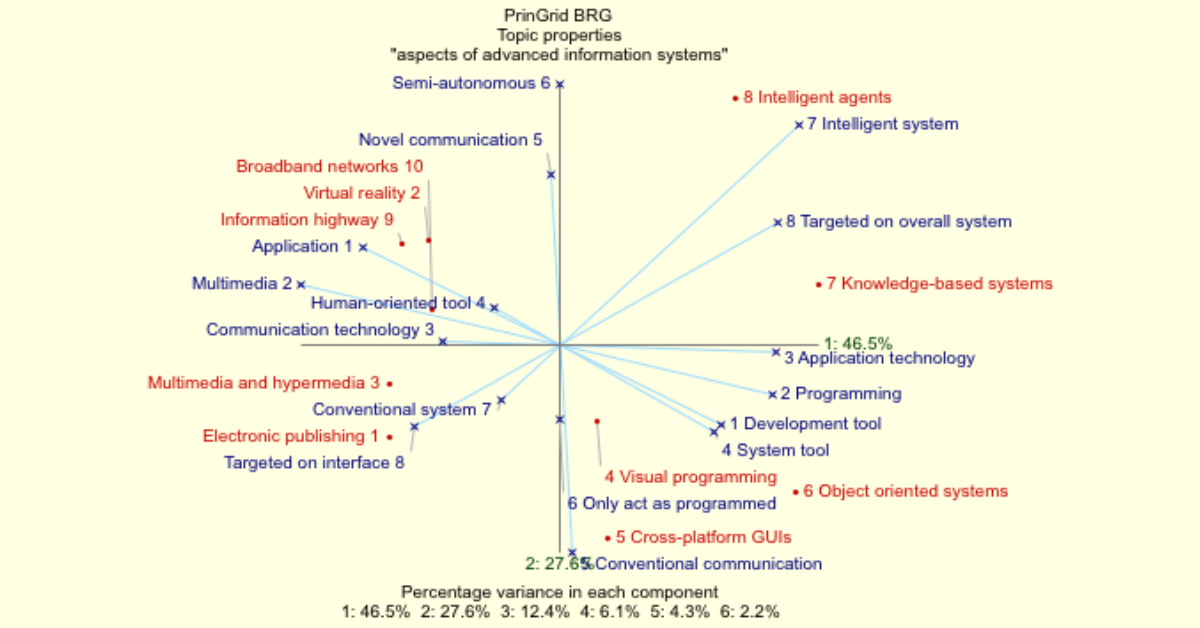

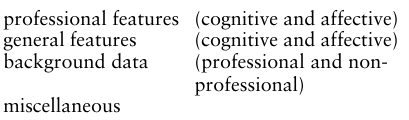

This second construct can be regarded as a dimension which is orthogonal to the first, and together they may form the axes for mapping the person’s psycho logical space. If we imagine the construct with the highest difference score to be ‘kind-cruel’ and the highest non-significant associated construct to be ‘confident-unsure’, then every other construct in the grid may be plotted with reference to these two axes.

The co-ordinates for the map are provided by the difference scores relating to the matching of each construct with the two used to form the axes of the graph. In this way a pictorial representation of the individual’s ‘personal construct space’ can be obtained, and inferences made from the spatial relationships between plotted constructs (see Data 19.6).

Mapping Psychological Space

By rotating the original grid 90 degrees and carrying out the same matching procedure on the columns (figures), a similar map may be obtained for the people (figures) included in the grid. Grid matrices can be subjected to analyses of varying degrees of complexity. We have illustrated one of the simplest ways of calculating relationships between constructs in Data 19.5. For the statistically minded researcher, a variety of programs exist in GAP, the Grid Analysis Package developed by Slater and described by Chetwynd (1974).1 GAP programs analyses the single grid, pairs of grids and grids in groups.

Grids may be aligned either by construct, by element or both. A fuller discussion of metric factor analysis is given in Fransella and Bannister (1977:73–81) and Pope and Keen (1981:77–91). Non-metric methods of grid analysis make no assumptions about the linearity of relationships between the variables and the factors.

Moreover, where the researcher is primarily interested in the relationships between elements, multidimensional scaling may prove a more useful approach to the data than principal components analysis. The choice of one method rather than another must ultimately rest both upon what is statistically correct and what is psychologically desirable. The danger in the use of advanced computer programmes, as Fransella and Bannister point out, is being caught up in the numbers game. Their plea is that grid users should have at least an intuitive grasp of the processes being so competently executed by their computers!

Strengths and Applications

Why Repertory Grid Works

It is in the application of interpretive perspectives in social research, where the investigator seeks to understand the meaning of events to those participating, that repertory grid technique offers exciting possibilities. It is particularly able to provide the researcher with abundance and a richness of interpretable material. Repertory grid is, of course, especially suitable for the exploration of relationships between an individual’s personal constructs as the studies of Foster (1992)2 and Neimeyer (1992), for example, show.

Foster employed a Grids Review and Organizing Workbook (GROW), a structured exercise based on personal construct theory, to help a 16-year-old boy articulate constructs relevant to his career goals. Neimeyer’s career counseling used a Vocational Reptest with a 19-year-old female student who compared and contrasted various vocational elements (occupations), laddering techniques being employed to determine construct hierarchies.

Real-World Applications in Education

Repertory grid is equally adaptable to the problem of identifying changes in individuals that occur as a result of some educational experience. By way of example, Burke, Noller and Caird (1992)3 identified changes in the constructs of a cohort of technical teacher trainees during the course of their two-year studies leading to qualified status.

In modified formats (the ‘dyad’ and the ‘double dyad’) repertory grid has employed relationships between people as elements, rather than people themselves, and demonstrated the increased sensitivity of this type of grid in identifying problems of adjustment in such diverse fields as family counseling (Alexander and Neimeyer, 1989) and sports psychology (Feixas, Marti and Villegas, 1989).

Finally, repertory grid can be used in studying the changing nature of construing and the patterning of relationships between constructs in groups of children from relatively young ages as the work of Epting et al. (1971), Salmon (1969) and Applebee (1976) have shown.

Challenges and Limitations

Technical vs. Theoretical Concerns

Fransella and Bannister (1977) point to a number of difficulties in the development and use of grid technique, the most important of which is, perhaps, the widening gulf between technical advances in grid forms and analyses and the theoretical basis from which these are derived. There is, it seems, a rapidly expanding grid industry. Small wonder, then, as Fransella and Bannister wryly observe, that studies such as a one-off analysis of the attitudes of a group of people to asparagus, which bears little or no relation to personal construct theory, are on the increase.

A second difficulty relates to the question of bi-polarity in those forms of the grid in which customarily only one pole of the construct is used. Researchers may make unwarranted inferences about constructs’ polar opposites. Yorke’s illustration of the possibility of the re searcher obtaining ‘bent’ constructs suggests the usefulness of the opposite method (Epting et al., 1971) in ensuring the bi-polarity of elicited constructs. A third caution is urged with respect to the elicitation and laddering of constructs. Laddering, note Fransella and Bannister, is an art, not a science. Great care must be taken not to impose constructs. Above all, the researcher must learn to listen to her subject(s).

Practical Problems in Implementation

A number of practical problems commonly experienced in rating grids are identified by Yorke.4 These are:

- Variable perception of elements of low personal relevance.

- Varying the context in which the elements are perceived during the administration of the grid.

- Halo effect intruding into the ratings where the subject sees the grid matrix building up.

- Accidental reversal of the rating scale (men tally switching from 5=high to 1=high, perhaps because ‘five points’ and ‘first’ are both ways of describing high quality). This can happen both within and between constructs, and is particularly likely where a negative or implicitly negative property is ascribed to the pair during triadic elicitation.

- Failure to follow the rules of the rating procedure. For example, where the pair has had to be rated at the high end of a 5-point scale, triads have been found in a single grid rated as 5, 4, 4; 1, 1, 2; 1, 2, 4 which must call into question the constructs and their relationship with the elements.

The Positivism Debate

More fundamental criticism of the repertory grid, however, argues that it exhibits a nomothetic positivism that is discordant with the very theory on which it is based. Whatever the method of rating, ranking or dichotomous allocation of elements on constructs, is there not an implicit assumption, asks Yorke, that the construct is stable across all of the elements being rated? Similar to scales of measurement in the physical sciences, elements are assigned to positions on a fixed scale of meaning as though the researcher were dealing with length or weight.

But meaning, Yorke reminds us, is ‘anchored in the shifting sands of semantics’. This he ably demonstrates by means of a hypothetical problem of rating four people on the construct ‘generous-mean’. Yorke shows that it would require a finely wrought grid of enormous proportions to do justice to the nuances of meaning that could be elicited in respect of the chosen construct. The charge that the rating of elements on constructs and the subsequent statistical analyses retain a positivistic core in what purports to be a non-positivistic methodology is difficult to refute.

Finally, increasing sophistication in computer-based analyses of repertory grid forms leads inevitably to a burgeoning number of concepts by which to describe the complexity of what can be found within matrices. It would be ironic, would it not, Fransella and Bannister ask, if repertory grid technique were to become absorbed into the traditions of psychological testing and employed in terms of the assumptions which underpin such testing. From measures to traits is but a short step, they warn.

Case Studies and Examples

Our first two examples of the use of personal constructs in education have to do with course evaluation, albeit one less directly than the other. The first study employs the triadic sorting procedure that Kelly originally suggested; the second illustrates the use of sophisticated interactive software in the elicitation and analysis of personal constructs. Kremer-Hayon’s (1991) study sought to answer two questions: first, ‘What are the personal constructs by which headteachers relate to their staff?’ and second, To what extent can those constructs be made more “professional”?’

The subjects of her research were thirty junior school headteachers participating in an in-service university program on school organization and management, educational leadership and curriculum development. The broad aim of the course was to improve the professional functioning of its participants. Headteachers’ personal constructs were elicited through the triadic sorting procedure in the following way: 1 Participants were provided with ten cards which they numbered 1 to 10. On each card they wrote the name of a member of staff with whom they worked at school. 2 They were then required to arrange the cards in threes, according to arbitrarily-selected numbers provided by the researcher.

Finally, they were asked to suggest one way in which two of the three named teachers in any one triad were similar and one way in which the third member was different. During the course of the two-year in-service program, the triadic sorting procedure was undertaken on three occasions: Phase 1 at the beginning of the first year, Phase 2 at the beginning of the second year, and Phase 3 two months later, after participants had engaged in a work shop aimed at enriching and broadening their perspectives as a result of analyzing personal constructs elicited during Phases 1 and 2.

The analysis of the personal construct data generated categories derived directly from the headteachers’ sorting. Categories were counted separately for each and for all headteachers, thus yielding personal and group profiles. This part of the analysis was undertaken by two judges working independently, who had previously attained 85 per cent agreement on equivalent data.

In classifying categories as ‘professional’ Kremer Hayon (1991) drew on a research literature which included the following attributes of a profession: ‘a specific body of knowledge and expertise, teaching skill, theory and research, account ability, commitment, code of ethics, solidarity and autonomy’. Descriptors were further differentiated as ‘cognitive’ and ‘affective’. By way of example, the first three attributes of professionalism listed above, (specific body of knowledge, teaching skills and theory and research) were taken to connote cognitive aspects; the next four, affective. Thus, the data were classified into the following categories:

At the onset of the in-service programme, the group of head-teachers related to their teaching staff by general rather than professional descriptors, and by affective rather than cognitive descriptors. The overall group profile at Phase 1 appeared to be non-professional and affective. This patterning changed at the onset of the second year when, as far as professional descriptors were concerned, a more balanced picture emerged. Upon the completion of the workshop (Phase 3), there was a substantial change towards a professional direction.

Kremer-Hayon concludes that the growth in the number of descriptors pertaining to professional features bears some promise for professional staff development. The research report of Fisher et al. (1991) arose out of an evaluation of a two-year diploma course in a college of further and higher education. Repertory grid was chosen as a particularly suitable means of helping students chart their way through the course of study and re veal to them aspects of their personal and professional growth. At the same time, it was felt that repertory grid would provide tutors and course directors with important feedback about teaching, examining and general management of the course as a whole. ‘

Flexigrid’, the interactive software used in the study, was chosen to overcome what the authors identify as the major problem of grid production and subsequent exploration of emerging issues—the factor of time. During the diploma course, five three-hour sessions were set aside for training and the elicitation of grids. Students were issued with a booklet containing exact instructions on using the computer. They were asked to identify six items they felt important in connection with their diploma course.

These six elements, along with the constructs arising from the triads selected by the software were entered into the computer. Students worked singly using the software and then discussed their individual findings in pairs, having already been trained how to interpret the ‘maps’ that appeared on the printouts. Individuals’ and partners’ interpretations were then entered in the students’ booklets. Tape-recorders were made available for recording conversations between pairs.

The analysis of the data in the research report de rives from a series of computer printouts accompanied by detailed student commentaries, together with field notes made by the researchers and two sets of taped discussions. From a scrutiny of all diploma student grids and commentaries, Fisher, Russell and McSweeney drew the following conclusions about students’ changing reactions to their studies as the course progressed.

1The over-riding student concerns were to do with anxiety and stress connected with the completion of assignments; such concerns, moreover, linked directly to the role of assessors. 2 Extrinsic factors took over from intrinsic ones, that is to say, finishing the course became more important than its intrinsic value. 3 Tutorial support was seen to provide a cushion against excessive stress and fear of failure. There was some evidence that tutors had not been particularly successful at defusing problems to do with external grading.

The researchers were satisfied with the potential of ‘Flexigrid’ as a tool for course evaluation. Particularly pleasing was the high level of internal validity shown by the congruence of results from the focused grids and the content analysis of students’ commentaries. For further examples of repertory grid technique we refer the reader to:

(a) Harré and Rosser’s (1975) account of ethogenically oriented research into the rules governing disorderly behaviour among secondary school leavers, which parallels both the spirit and the approach of an extension of repertory grid described by Ravenette (1977)

(b) a study of student teachers’ perceptions of the teaching practice situation (Osborne, 1977) which uses 13×13 matrices to elicit elements (significant role incum bents) and provides an example of Smith’s and Leach’s (1972) use of hierarchical structures in repertory grids.

Grid Technique and Audio/Video Lesson Recording

Parsons et al. (1983) show how grid technique and audio/video recordings of teachers’ work in classrooms can be used to make explicit the ‘implicit models’ that teachers have of how children learn. Fourteen children were randomly selected and, on the basis of individual photographs, triadic comparisons were made to elicit constructs concerning one teacher’s ideas about the similarities and differences in the manner in which these children learned.

In addition, extensive observations of the teacher’s classroom behaviour were undertaken under naturalistic conditions and verbatim recordings (audio and video) were made for future review and discussion between the teacher and the researchers at the end of each recording session. What very soon became evident in these ongoing complementary analyses was the clear distinction that Mrs C (the teacher) held for high and low achievers.

The analysis of the children in class as shown in the video tapes revealed that not only did high and low achievers sit in separate groups but the teacher’s whole approach to these two groupings differed: With high achievers, Mrs. C would often adopt a ‘working with’ approach, i.e. verbalizing what children had done, with their help. When con fronted with low achievers, Mrs. C would more often ask ‘why’ they had tackled problems in a certain manner, and wait for an answer. (Parsons et al., 1983).

Modern Innovations

Computer-Based Analysis Tools

A number of developments have been reported in the use of computer programmes in repertory grid research. We briefly identify these as follows:

Focused Grids and Non-Verbal Applications

1 Focusing a grid assists in the interpretation of raw grid data. Each element is compared with every other element and the ordering of elements in the grid is changed so that those most alike are clustered most closely together. A similar rearrangement is made in respect of each construct.

2 Physical objects can be used as elements and grid elicitation is then carried out in nonverbal terms. Thomas (1978) claims that this approach enhances the exploration of sensory and perceptual experiences.

Exchange Grids and Sociogrids

3 Exchange grids are procedures developed to enhance the quality of conversational exchanges. Basically, one person’s construing provides the format for an empty grid which is offered to another person for completion.

The empty grid consists of the first person’s verbal descriptions from which his ratings have been deleted. The second person is then invited to test his comprehending of the first person’s point of view by filling in the grid as he believes the other has already completed it. Various computer programmes (‘Pairs’, ‘Cores’ and ‘Difference’) are available to assist analysis of the processes of negotiation elicited in exchange grids.

In the ‘Pairs’ analysis, all constructs in one grid are compared with all constructs in the other grid and a measure of commonality in construing is determined. ‘Pairs’ analysis leads on to ‘Sociogrids’ in which the pattern of relationships between the grids of one group can be identified. In turn, ‘Sociogrids’ can provide a mode grid for the whole group or a number of mode grids identifying cliques. ‘Socionets’ which reveal the pattern of shared construing can also be derived.

With these brief examples, the reader will catch something of the favour of what can be achieved using the various manifestations of repertory grid techniques in the field of educational research.

Read More:

https://nurseseducator.com/didactic-and-dialectic-teaching-rationale-for-team-based-learning/

https://nurseseducator.com/high-fidelity-simulation-use-in-nursing-education/

First NCLEX Exam Center In Pakistan From Lahore (Mall of Lahore) to the Global Nursing

Categories of Journals: W, X, Y and Z Category Journal In Nursing Education

AI in Healthcare Content Creation: A Double-Edged Sword and Scary

Social Links:

https://www.facebook.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.instagram.com/nurseseducator/

https://www.pinterest.com/NursesEducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/nurseseducator/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/nurseseducator/

https://x.com/nurseseducator?t=-CkOdqgd2Ub_VO0JSGJ31Q&s=08

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Afza-Lal-Din

https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=F0XY9vQAAAAJ